Iqaluit workshop brainstorms how to reduce poverty in the city

“We must start working on it”

About 80 Iqaluit residents attended a March 30 workshop in the Anglican parish hall on how to reduce poverty in the city. (PHOTO BY JANE GEORGE)

Inuit in Iqaluit often lack the support structure seen in small Nunavut communities, Saa Kotairuq of Iqaluit tells a March 30 poverty reduction workshop in Iqaluit. (PHOTO BY JANE GEORGE)

How to reduce poverty in Iqaluit— that’s the task tackled by 80 people at a March 30 workshop in Iqaluit.

Their goal: the creation of Nunavut’s first anti-poverty strategy.

This workshop, similar to others held throughout Nunavut, marks step one in the Nunavut-wide “public engagement process” on poverty reduction, first announced by the Government of Nunavut and Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. last October.

By 2030, Premier Eva Aariak has said she envisions a Nunavut where all residents understand the Inuit language, where no one lives in poverty or goes hungry, and where all residents prosper within an economy driven by resource development and the marketing of Inuit cultural production in film, music, literature, art, music, and fashion.

The three-hour evening workshop in Iqaluit’s Anglican parish hall gave ordinary citizens a chance to say how they would fight poverty in the city.

That’s good, because poverty reduction in Nunavut will depend on people— not just governments or organizations, said Natan Obed, director of NTI’s department of social and cultural development, who took part in the workshop.

The workshop format succeeded in involving all those who showed up.

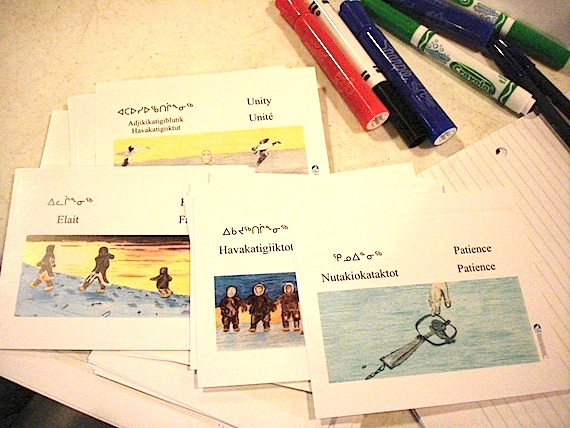

First, organizers asked everyone sitting at tables around the room to pick a card showing an image and a word, which they feel are important in their own life and to society.

They picked among cards with words — written in Inuktitut, Innuinaqtun, English and French — like “perseverance,” “improvisation” and “volunteer.”

Robin Anawak chose a card that read “taking the big view”— because, he said, there would be “no quick fixes” to ending poverty in Iqaluit.

For Jesse Tungilik, the word of the evening was “conservation” because he wants to see a sustainable future for Iqaluit.

“Cooperation” was the word for Monte Kehler, president of Iqaluit’s homeless shelter board, who said reducing poverty needs cooperation from all levels of government.

For Sarah Minogue, a journalist turned stay-at-home mother, who came with her two-month-old daughter, the choice was “family.”

But choosing these cards was just the beginning.

Participants were then asked to write down what they see as Iqaluit’s assets, things they don’t want to change about Iqaluit— like its elders, Tukisigiarvik centre, diversity, infrastructure, cellphone service, government presence, youth centre, fish — and even Tim Hortons, as one suggested.

And those at the various tables discussed their visions for Iqaluit’s future, asking how can they build that better future without poverty, where Iqaluit is a cleaner, more friendly place, with homes for everyone, and more social supports, a city, where everyone has enough to eat and a place to sleep?

Suggestions for getting there included electing socially-responsible leaders and then keeping them accountable, increasing educational opportunities, and providing more support for healing because “there are a lot of things that are keeping people down” in cycles of violence and addictions.

Some practical suggestions included setting up community freezers, on-the-land camps, more and better housing, a social development centre, and public transit.

Improving food security topped many tables’ lists of how to reduce poverty.

That was also the message from participant Saa Kotiaruq.

Kotairuq told the workshop that she came there thinking it would be a meeting on how Income support recipients could improve their living conditions.

She said she was surprised — but happy— to see so many people talking about the larger issue of poverty reduction.

People need more help and good food to thrive, because many Inuit like her come from other Nunavut communities and lack family support, she told the group.

Kotairuq’s input and that of others of the Iqaluit meeting are the start of anti-poverty process, which will continue at least for the next three years, said Ed McKenna, director of Nunavut’s poverty secretariat.

“Poverty isn’t something we’re going to eliminate this year, or even in 20 years, but we must start working on it,” McKenna said in a March 31 interview. “It’s a process we’ve started, and a commitment we’re making to the public.”

Ideas from the community workshops and focus groups will feed into a series of roundtables on poverty reduction to be held in Cambridge Bay, Iqaluit, Rankin Inlet and Pond Inlet this May.

Each region will propose options for action.

Then, in the fall of 2011, the GN will convene a two-day poverty summit in Iqaluit to develop a poverty reduction action plan.

People in Iqaluit who missed the March 30 poverty workshop can go to Abe Okpik Hall in Apex on April 4 at 6:30 p.m. to take part in a similar workshop.

Participants at a March 30 poverty reduction workshop in Iqaluit started off their discussions by choosing among cards showing words they think are important in life and society. (PHOTO BY JANE GEORGE)

(0) Comments