A Nunavut tragedy—Part One: The Victim

“We still cry at his daughter’s Christmas concerts”

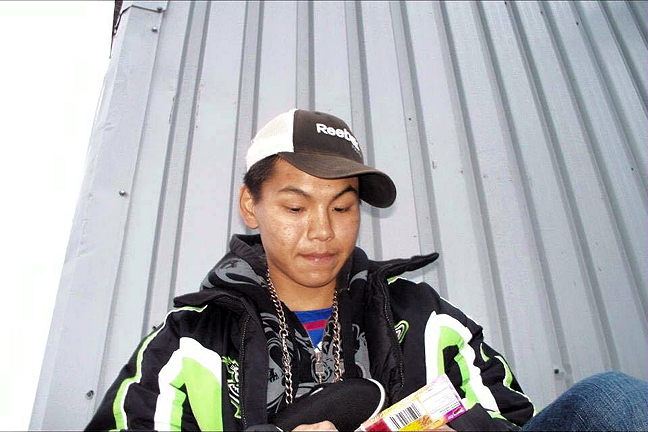

In one of the last photos taken of Mappaluk Adla alive, you can see the scar left behind after a jealous man attacked Adla with a metal pipe, fracturing his skull. (PHOTO COURTESY ETTULA ADLA)

Mappaluk Adla wearing his Kinngait colours, in this undated hockey photo. (PHOTO COURTESY ETTULA ADLA)

Mappaluk Adla died of a single gunshot wound to the head on Sept. 20, 2010. He was 22. It was his 18-year-old stepbrother, Peter Kingwatsiak, who pulled the trigger. (PHOTO COURTESY ETTULA ADLA)

On Sept. 20, 2010, after huffing gasoline several times that night, Peter Kingwatsiak, 18, killed his stepbrother Mappaluk Adla, 22, with a single gunshot to the head while Adla slept on the living room couch in his home in Cape Dorset, a Nunavut community of about 1,300 on south Baffin Island.

In 2016, a Nunavut judge convicted Kingwatsiak of first-degree murder and sentenced him to life in prison with no parole eligibility for 25 years.

In this three-part investigative series, Nunatsiaq News draws on court documents and interviews to focus on the human lives touched by this violent death: the victim, the killer, their families and communities.

Mappaluk Adla was a father of three when his stepbrother, Peter Kingwatsiak, killed him.

His youngest, a daughter, was only two. He loved to teach his princess how to brush her teeth. Having good teeth was important to Adla.

That little girl will never know her father because of what Kingwatsiak did, Adla’s mother, Kumaarjuk Pii, said at Kingwatsiak’s sentencing in Cape Dorset’s community hall in June.

“We still cry at his daughter’s Christmas concerts because he’s not there to see his princess at special occasions.”

The story of Kingwatsiak and Adla is a story about Inuit families fractured by violence from within. It’s a story about Inuit men with such anger, confusion and hurt, they turn on themselves, each other, their friends and their families. And it’s a story about the justice system’s apparent inability to curb that violence.

The roots of this story reach back to the 1950s, when Inuit society experienced a rapid, drastic change from a traditional hunting lifestyle towards a life embedded in modern Canadian society.

Many Inuit men found themselves on the margins of a wage economy, unable to provide for their families as they once did. Feelings of uselessness, powerlessness and despair grew, and, for many Inuit men, persist today.

The trail leading toward Adla and Kingwatsiak’s story is littered with the stories of countless broken Inuit men, many of whom lash out in violence.

Numbers alone can tell the story: Nunavut’s Crime Severity Index, which weighs the seriousness and rate of violent crimes, is five times higher than the national average, with the violent crimes committed overwhelmingly by men.

Domestic violence rates in Nunavut are nearly 12 times higher than the Canadian average, about 42 per cent higher than anywhere else in the country. Inuit women and children are overwhelmingly the victims of that domestic violence.

And young Inuit men—who, between the ages of 15 and 24, have died by suicide at a rate over 40 times the national average in the past 15 years—are also four times more likely to face arrest than the average Canadian.

But the story of Kingwatsiak and Adla is also about family, love, community and resilience; and about the search for forgiveness and atonement.

It’s about how in Nunavut loved ones die far too young time and again as shattered hearts look on through unbelieving eyes. Grief drains all tears. So people just go on.

Mappaluk Adla

Adla was a fighter, his mother Kumaarjuk Pii said at Kingwatsiak’s sentencing in June.

“This is my only chance to describe my son, so I’m just going to go all out,” she told the judge.

Pii called Adla her “miracle baby,” because he was conceived in her fallopian tube, where pregnancies can be fatal to both mother and baby. She believes prayer sent him on a journey to her uterus.

“Things that he battled in his way-too-short-life were what made him strong, and that’s what made him have compassion for others,” Pii said.

Like when, as a teenager, Adla would ask his mother if friends could stay over because their parents were drunk and fighting at home. He had a big heart and a bigger smile. When Adla smiled—big white teeth showing through open lips—it made you want to smile.

Adla was persistent, even as a child. Once, when he was six, he cried for three hours straight after learning he was too young to register for hockey.

“After three hours of listening to him cry, his crying paid off. He melted the coach’s heart [who] said let him register,” Pii said.

He wasn’t an angel, but he loved his family, Adla’s mom said. At age seven, he tried to commit suicide for the first time. After his last suicide attempt, he promised his mom never to try again.

“Mum I love you and I wouldn’t want you to be in such pain about me,” Pii remembered her son telling her. Adla kept that promise.

Adla’s brother, Ettula Adla, said he often had to defend his brother against other jealous boys growing up. A month before Kingwatsiak killed Adla, Ettula said his brother was “brutally beaten up with a metal pipe that fractured his skull,” by a guy who was jealous of him.

“He always had jealous guys going after him most of his teen and adult life,” Ettula said. “He was so friendly and was everybody’s friend.”

The last picture of Adla, taken at his autopsy, shows a young Inuk with big eyes under bruised eyelids and wide black eyebrows, the hairless skin of his face a soft creamy brown.

A light reflects from his skin that makes it seem to glow. He looks younger than 22.

In the corner of Adla’s left eye, his tear duct had filled with blood and a red tear-shaped bead formed. The only other blemish on Adla’s face was a small round bullet hole in the middle of his forehead.

Perhaps the one comfort Pii can find in the death of her son is that Adla died almost instantly, as anyone shot point blank in the head almost always does.

But, like many other Inuit, Adla’s mother has lost so many loved ones that you are left wondering: how much can one woman suffer?

Her first husband, Adla’s father, was stabbed to death in 2001. Pii wrote a letter to the newspaper asking readers to pray for her family and the family of the woman who killed her ex-husband.

Two years later, Pii wrote another letter after her younger brother died by suicide.

“My dear beloved Kai Kumu, I want to tell you to rest in peace but I won’t because you were chained for too long while you were with us. You were at last free. So I hope that you are soaring the skies.”

Today, Pii tries to love and forgive the boy who killed her miracle baby.

“For my own sanity, and because I still love you Peter, I want to forgive you. But I can only do that by the grace of God,” she said to Kingwatsiak moments before he was sentenced to life in prison.

Still, Pii lives with the “horrendous nightmare” of Adla’s death.

“After his death I went emotionally numb and kept all my pain inside, because to feel pain was like dying inside.”

Kumaarjuk said her heart breaks every time she remembers how Adla’s older brother, Ashevak, carried Adla’s lifeless body to the RCMP vehicle.

“How strong he had to be do that. It’s no wonder he said his legs gave out and he almost dropped his brother’s body.”

You can read the second instalment in this series, A Nunavut tragedy—Part Two: The Killer, here.

You can read the third, A Nunavut tragedy—Part Three: The Broken Men, here.

Mappaluk Adla, right, with one of his best friends growing up on Cape Dorset, Christopher Johnson Hayward. (PHOTO COURTESY ETTULA ADLA)

(0) Comments