Community-wide TB screening effort in Nunavut involved 100 health workers: researcher

Details of Qikiqtarjuaq campaign surface at International Congress on Circumpolar Health

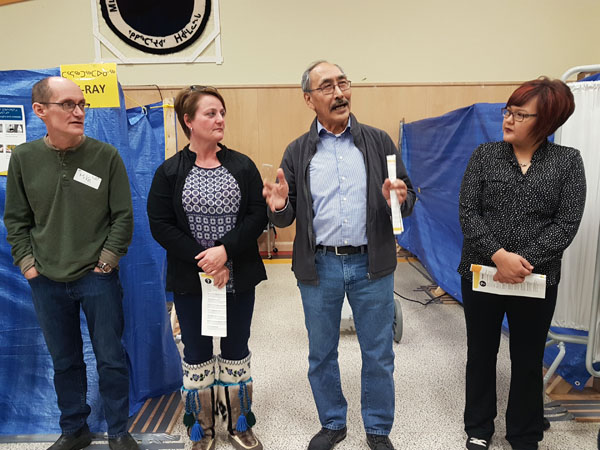

From the left you can see Dr. Mike Patterson and Nunavut Health Minister Pat Angnakak, along with Nunavut’s former premier Paul Quassa and his executive secretary Kailey Arreak, as they help launch a community-wide screening campaign in Qikiqtarjuaq last February. A better idea of what that community-wide screening effort required was provided at an Aug. 13 session during the International Congress on Circumpolar Health in Copenhagen. (FILE PHOTO)

COPENHAGEN—The Government of Nunavut and the federal government deployed roughly 100 health personnel to Qikiqtarjuaq for a military-like public health operation earlier this year, during which they commandeered the community centre for a fully equipped medical clinic and laboratory.

Their goal: to tackle an outbreak of tuberculosis in this Baffin community of about 600 and look at whether this kind of effort could eradicate the potentially deadly infectious disease in Nunavut.

Some details of the community-wide screening effort were made available to Nunatsiaq News at the time.

But, in Copenhagen, at the International Congress on Circumpolar Health now underway until Aug. 16, Andrea Schertzer of the Public Health Agency of Canada shared much more of the background and results of that six-week-long campaign at a conference session on Monday.

Schertzer also works with Nunavut’s Health Department in Iqaluit.

During her presentation at the conference, she said some of the 100 or so health professionals who participated in the Qikiqtarjuaq screening came from outside Nunavut, with doctors brought in from Winnipeg and Ottawa. Nurses from the Toronto Public Health and London-Middlesex Health units and from other Nunavut communities were also “mobilized to help,” Schertzer said.

That’s in addition to respiratory therapists and X-ray technicians who, along with the others, set up shop in the community centre. Their equipment included a GeneXpert TB-tester machine and an x-ray machine.

The screening, which took place from Feb. 5 to March 16, came after the territory had suffered one of its worst years for active or latent cases of TB since 1999, with about 100 cases in 2017, the same number reported in 2010.

From January 2016 to December 2017, 40 new cases of TB were diagnosed in Qikiqtarjuaq, Schertzer said, with 70 per cent of the cases being among children and youth.

Ileen Kooneeliusie, a 15-year-old from Qikiqtarjuaq who had TB, died of the infectious disease in Jan. 2017.

But Schertzer did not link the big screening effort to Kooneeliusie’s death. Schertzer only mentioned that there had been a death from TB in 2017 in Qikiqtarjuaq.

Schertzer said the community-wide screening was designed to respond to the high number of new active cases detected in Qikiqtarjuaq.

The goal, she said, was to find all other active cases and find and treat new, previously untreated cases.

To do that, community leaders and health care staff reached out to people to participate in the screening. Many had already been tested before and suffered from “screening fatigue.” To encourage people to come forward, they offered $25 food vouchers for people who participated in the screening.

The organizers wanted to screen 531 people, but, in end, 44 people were not screened either because they had moved or refused to participate.

The doctors and nurses found 12 active TB cases: four under the age of five, one in the five-to-14-year age group, three in the 24-to-35 age group and four in the 35-and-older age bracket. They also found 24 new latent infections.

More than 100 new prescriptions for TB treatment medications were handed out, Schertzer said.

But operations during the screening weren’t all smooth: there was a lack of housing for the team, along with 10-hour workdays and, later, lots of additional work required to evaluate the results, Schertzer said.

Not surprisingly, there were also problems with recording everything electronically and “some of our data collection were not ideal,” she said.

As well, in Qikiqtarjuaq, there are now many people on treatment who need follow-up care.

The cost-effectiveness of the screening campaign is now being evaluated, Schertzer said.

TB remains 50 times higher in Nunavut than in rest of Canada, she said.

This past March 23, in Ottawa, one day ahead of World Tuberculosis Day, Indigenous Services Minister Jane Philpott and Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami President Natan Obed announced the goal to eliminate TB across Inuit Nunangat by 2030, and reduce the rate of active TB by at least 50 per cent by 2025.

“The rate of TB is outrageous,” Philpott said, “but it is eminently solvable.”

But another presenter at the Copenhagen health conference, Ginette Thomas, a recent PhD graduate from Carleton University, put the blame on the federal government for that disparity, saying it was “the policies themselves that are responsible the continued inequalities.”

These included managing TB for Inuit as a “humanitarian” gesture instead of an obligation, she said.

(0) Comments