New Iqaluit port aims for more sealift efficiency, safety

GN hopes separate small craft harbour improves conditions for boaters

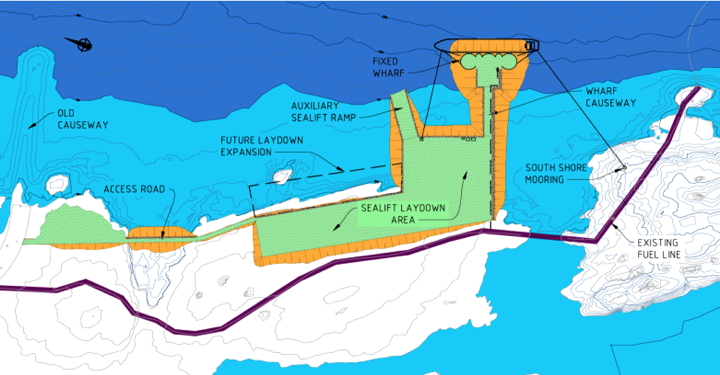

Iqaluit’s deep-sea port will be located at the southwestern tip of Koojesse Inlet. Its features, shown in orange and green in this image, will include a fixed dock where cargo ships will unload their freight and a sealift ramp to unload barges. (IMAGE FROM GOVERNMENT OF NUNAVUT)

Once Iqaluit’s deep-sea port opens in 2021, the city’s beachfront will no longer feature crowded scrambles on sand like this one, from the sealift season of 2014. (PHOTO BY PETER VARGA)

Plans for a deep-sea port in Iqaluit by the year 2021 promise to eliminate what amounts to a summer-long D-Day-like supply operation on Iqaluit’s beachfront, otherwise known as the sealift, during the brief ice-free period between June and October.

Meanwhile, related plans for a small craft harbour on the opposite side of Koojesse Inlet are meant to improve access to the sea for boaters over the same period.

Nunavut’s Department of Community and Government Services, which is directing the projects, expects construction of the port to finish by the end of fall 2020, and start operation for the sealift season of 2021.

The deep-sea port took a big step toward reality when the federal government approved financing for it through the Building Canada Fund in 2015.

Some $63.7 million of the total $84.9 million project approved at the time for both the port and the small craft harbour still stands.

The Government of Nunavut will contribute the remaining $21.2 million, according to the Department of Community and Government Services (CGS).

“We probably are at an actual 10-per cent completion on the actual design,” of both the port and the small-craft harbour, said Paul Mulak, director of capital projects for CGS.

“We’re much further on the environmental approval process,” he said. They expect the Nunavut Impact Review Board will approve the project by the end of this year.

A global consulting firm, Advisian, is carrying out all engineering work.

The port will take up about 40,000 square metres of space, constructed at South Polaris reef, an area at the southwestern tip of Koojesse Inlet near the end of the fuel line where seafaring tankers supply the city.

Cargo ships will unload their contents primarily at a large dock in deep water where boats can come and go at any time of day, regardless of the tides.

An auxiliary sealift ramp next to the large fixed wharf will allow cargo vessels to unload by barge, much as they do today—but at all times of the day, Mulak said.

Ships will deposit their cargo at a laydown area that takes up most of the port’s space. Cargo can then be trucked from there into the city.

The deep-sea port’s main priority is to improve the efficiency and safety of the marine cargo re-supply in Iqaluit. Pushing barges up to the beach during high tide, as is the case now, “is certainly very subjective to weather, ice conditions and tide conditions,” Mulak said.

Shipping companies only have a limited window in which to take barge-loads of cargo to the beachfront area by the city’s core—basically a few hours during high-tide conditions

“It’s at least a five-day to 10-day operation to unload one of those cargo vessels, depending on the weather,” said Mulak. Barge transport in and out of the bay must also contend with more safety hazards than simply unloading at a fixed wharf or ramp perched next to deep water, he added.

“The expectation is that the offload time would be four to five times better than what it is today. So something that takes five days today, in good weather conditions, would probably take only a day,” he said.

The dock would function within the same season as the current sealift, from late June to early October.

Mulak, oversees the project for CGS, said only time will tell if the port will actually decrease the cost of shipping to Iqaluit.

“Certainly, we’re not expecting to see significant changes to costs immediately,” he said.

Changes to the cost of shipping will ultimately depend on decisions by shipping companies.

Many vessels that come into Iqaluit continue on to other Baffin communities, he said.

“If they continue to do that, they will still need to take their barges and their heavy equipment to unload in other communities. I think some of the expectation is that we will see more and more vessels coming into Iqaluit that only contain Iqaluit cargo,” Mulak said. “And that may at some point have some impact on cost.”

The CGS shared plans for the deep-sea port and small craft harbour with Iqalungmiut at an open house earlier this month, March 2 and March 3.

Residents expressed support for the marine infrastructure project overall, tempered by concerns about safety and access to the sea for boating activities during the project’s construction phase, Mulak said.

Concerns centred around work to the small craft harbour, which the CGS says will overlap with the construction of the port—from summer of 2018 to late-fall 2020.

Small craft harbour improvements

The department describes the small craft harbour segment as a set of “improvements” to Iqaluit’s breakwater—a structure now used as a boat-launch and docking area where small vessels are beached during low-tide periods.

Plans call for construction of a deeper basin that could allow boats access to the sea at lower tide levels, a new storage and parking area, improvements to the boat ramp and installation of small craft floats.

“The demographics of all the recreational boating in Iqaluit are quite broad,” Mulak said. They range from residents with small boats, who keep them on the beach, to others with large boats launched off trailers, and others who keep larger boats in deeper water.

“The small craft harbour has to try to serve all of those needs,” the project director said.

Recreational boaters also make use of an old, eroded causeway on the other side of the bay, close to the future site of the port facility.

Staff with the CGS have heeded suggestions to create a boaters’ association working group to represent the “full spectrum of recreational boaters in Iqaluit, and get some direct input into the design,” Mulak said.

In consultation with the group, the department will “ideally come up with a design that really works for all the different segments of boaters in Iqaluit,” he said.

Preliminary plans also call for minor improvements to the causeway, Mulak added, which “plays a relatively important role” at providing access to the water.

The department will open a second round of public consultations on the marine infrastructure projects “in a few months,” he said.

Improvements to the small craft harbour in Iqaluit, shown in this image, include a deeper boat basin, shown in dark blue, to allow recreational boaters easier access to the sea, and construction of a new parking area, boat ramp, and small craft floats. (IMAGE FROM THE GOVERNMENT OF NUNAVUT)

(0) Comments