Parks Canada releases new images of 2017 Franklin dives in Nunavut

“Parks Canada’s Underwater Archaeology team was able to locate previously unseen artifacts”

The ship’s wheel of the HMS Terror, in 2016.

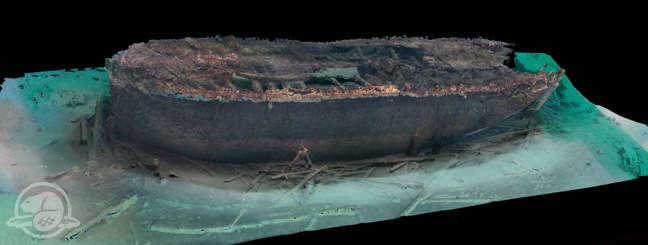

A port-side 3D scan of the HMS Erebus on the ocean floor of Queen Maud Gulf in Nunavut. (IMAGES COURTESY OF PARKS CANADA)

A Parks Canada underwater archaeologist examines the site of the HMS Erebus in August 2017.

New details about Sir John Franklin’s doomed Arctic expedition continue to be discovered as archeologists examine two sunken wrecks in Nunavut’s waters.

Following the announcement that the United Kingdom would transfer the shipwrecks to the country that offered them a final Arctic resting place, Parks Canada has released a new trove of underwater images of HMS Terror and HMS Erebus taken this past summer.

New images confirm that the Terror’s anchor remains on board, disproving earlier speculation from 2016 that the ship was “at anchor” when it sank—another important detail as researchers determine the timeline of events in this historic tragedy.

As well, Parks Canada says it has catalogued 64 artifacts from the Erebus, but added that no artifacts were removed from either the Erebus or Terror during the 2017 expedition.

“Through dives, Parks Canada’s Underwater Archaeology team was able to locate previously unseen artifacts, including wine bottles, on the wreck [of the Erebus],” said Parks Canada communications officer Meaghan Bradley.

The British government’s proposed transfer of the wrecks to Canada would be in exchange for “a small sample of artifacts,” the United Kingdom said in a statement.

What will be contained in that sample of artifacts has yet to be specified but Parks Canada said it “looks forward to working with the United Kingdom in the very near future to finalize the details of the artifact transfer.”

This year marks the first Franklin search season in 172 years since the location of both wrecks was known, and where the primary objective for searchers was not to find the wrecks, but to spend their precious field time filling in the gaps in one of the 19th century’s most captivating mysteries.

Sir John Franklin and 128 crewman under his command departed England on May 19, 1845 aboard the Terror and Erebus, charged by the British Admiralty to chart safe passage through Canada’s Arctic Islands to the Pacific Ocean.

But tragedy struck after the expedition’s first winter, when the ships became trapped in thick, year-round sea ice northwest of King William Island.

The final entry on a note recovered in a cairn on King William Island, dated in 1848, said the Franklin crew members—Franklin himself was dead by this point—were pushing south on foot to Back River in what was presumed to be a hopeless attempt to reach the nearest Hudson Bay Co. outpost, hundreds of kilometers away.

But now that the location of the Terror and Erebus are known, that might not be the whole story.

New sonar imagery released by Parks Canada shows the first full views of the Erebus standing upright on the ocean floor of the Queen Maud Gulf, matching earlier descriptions from Parks Canada divers as being “remarkably well preserved.”

Its location, in an area Inuit call Utjulik, is well over 100 kilometres from where many western historians traditionally expected the Erebus to be, and proved that contemporary historical Inuit testimony recorded by figures like Charles Hall in the 1860s were, in fact, accurate.

Hall, as well as modern Inuit historian Louie Kamookak, told stories of Inuit going aboard abandoned ships that contained corpses stowed in bunks, along with other instances where they may have met and communicated with officers.

The existing historical evidence, however, has yet to fully corroborate that these accounts relate to Franklin’s expedition.

But the fact that the wrecks rest in locations that do not match the last known co-ordinates given by Franklin’s crew in the Victory Point cairn note suggests that the doomed crew may have survived longer than many thought, and may have even returned to the ships after departing for Back River.

Russell Potter, author of Finding Franklin: The Untold Story of a 165-Year Search, believes that the final resting place of the wrecks prove the Victory Point cairn note is “anything but a last note.”

“Whether re-manned or re-inhabited [the location of the wrecks] change the whole story,” he told Nunatsiaq News, Oct. 27.

But there is no way of creating a complete timeline without written records, which Potter believes could still be resting somewhere inside the Erebus and Terror.

“Written records alone can really answer the question, and there’s every reason to expect some will be found on the wrecks,” Potter said.

Perhaps more answers will be revealed during future visits, when researchers return to the wrecks in 2018.

Parks Canada scaled back plans for a more extensive search and excavation of the wrecks in 2017 after their research vessel, the David Thompson, was forced to spend additional time in dry dock for repairs.

An overhead scan of the HMS Erebus showing the ship with surrounding debris and artifacts.

(0) Comments