Shipping traffic swells in Canadian Arctic as sea ice shrinks

Distance travelled by ships nearly tripled over 25 years

A yacht is spotted in Cambridge Bay in 2005. While cargo ships and government icebreakers make up most of the Canadian Arctic’s ship traffic, the fastest-growing category of vessel consists of small pleasure craft like this, concentrated in the Northwest Passage during the summer. (IMAGE COURTESY OF EMMA STEWART)

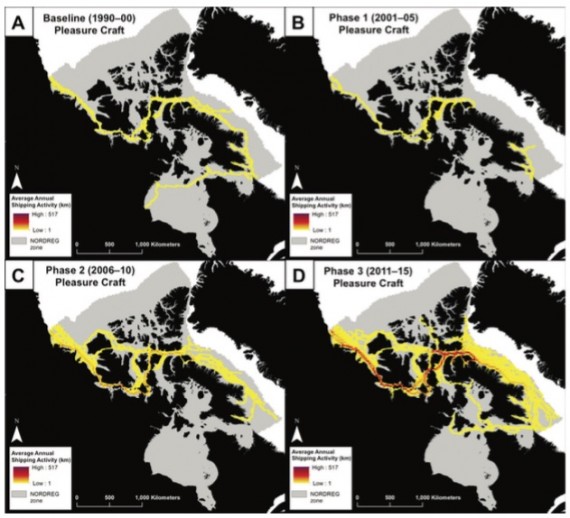

This image, from a study published this month in the scientific journal Arctic, charts the growing use of small pleasure craft in Canadian Arctic waters between 1990 and 2015.

This graphic shows how fishing vessels have in recent years expanded northwards into Lancaster Sound and as far west as Resolute Bay and Little Cornwallis Island, as well as southwards, with greater activity in Hudson Strait and southern Baffin Island.

As Arctic sea ice melts, the distance travelled by ships in the Canadian Arctic has nearly tripled over the past 25 years.

And with shipping traffic down in the Northwest Territories due to the decline in oil and gas exploration, the bulk of this activity is concentrated in Nunavut’s waters.

That’s according to research published this month in the scientific journal Arctic.

Cargo vessels and government icebreakers continue to make up most of the Arctic’s ship traffic. But the fastest growing type of vessel is, in fact, yachts.

“Yachts have gone up 400 per cent,” said Jackie Dawson, a researcher with the University of Ottawa and the lead author of the paper.

“We don’t pay attention to yachts. We pay attention to the Snow Dragon,” she said, referring to the Chinese icebreaker that recently traversed the Northwest Passage, “which is also important.”

These pleasure craft include “everything from little sailboats full of crazy adventure people to multi-million-dollar luxury yachts,” said Dawson.

“It’s everything from people trying to set records to really wealthy people going there because they can.”

Her paper notes these small vessels tend to concentrate inside the Northwest Passage, but have also been found “venturing farther north than ever before, and are forging new and unique routes along the western side of Baffin Island.”

Fishing boats are also operating in new areas off the eastern coast of Baffin Island, expanding northwards into Lancaster Sound and as far west as Resolute Bay and Little Cornwallis Island, as well as southwards, with greater activity in Hudson Strait and southern Baffin Island.

Pond Inlet is the Nunavut community that’s seen the biggest increase in shipping traffic since 1990, due to fuel tankers and bulk carriers servicing Baffinland’s nearby Mary River iron mine, as well as passing cruise ships.

Chesterfield Inlet and Baker Lake saw the next biggest increases in ship traffic, related to tankers and cargo ships servicing the Meadowbank gold mine.

Cambridge Bay also saw a big increase, with growing numbers of yachts, cruise ships, cargo ships and tankers travelling within the Northwest Passage.

Resolute Bay, meanwhile, was one of the few communities to see shipping traffic drop since 1990, likely as a result of the closure of the Nanisivik and Polaris mines, which both shut in 2002, and due to a tendency of sea ice to clog the area’s shipping routes.

The paper predicts that communities in Nunavut’s Hudson Bay region will see a reduction of ship traffic in the future, due to the closure of the port of Churchill, Manitoba, in 2017.

It’s important to not overstate the increase in shipping in the Canadian Arctic, Dawson said in an interview. Parts of Canada’s Northwest Passage are expected to remain unpredictably ice-clogged for decades to come. These conditions make the passage much less accessible than Russia’s Northern Sea Route.

But, in the long term, Dawson said you can count on shipping in the region to continue to grow.

“It may not go up in 20 years, but 20 years isn’t that long,” she said. “And it’s definitely going up in 100, unless there’s something catastrophic that happens, climatically. And when we get to that point, we will see trade through the Arctic.”

New technology, such as the next generation of icebreakers being built by countries like China and Korea, could also end up being game-changers.

“These vehicles are sophisticated and sometimes autonomous,” said Dawson. “And this ice pack, which we’ve used as an excuse to not go through the Arctic, will no longer be relevant when we have certain new technologies.

“It’s a balance between being not alarmist, but understanding that it is coming, and taking the time to make sure that the measures are in place to protect these places in a way that Canada sees fit.”

Dawson is helping with that. She is involved with ongoing work with the Canadian Coast Guard to help develop low-impact shipping corridors in the Canadian Arctic.

She’s also starting a project to look at how to manage shipping impacts through two sensitive sites: Lancaster Sound and the area near the Franklin wrecks.

The good news, when it comes to the long-term increase in Arctic shipping, is that Canada has time to prepare, she said.

“We’re in the lucky position to be proactive,” Dawson said. “We have time.”

(0) Comments