New World’s first humans may have come via Arctic

Did the original inhabitants of the Americas take a detour through Nunavut?

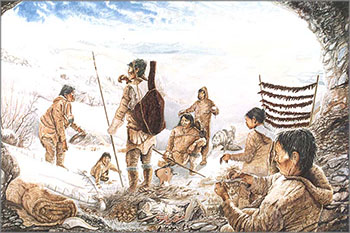

Two scientists from the University of Utah argue that the first humans to inhabit the Americas may have arrived as early as 30,000 years ago, then headed south after travelling through the High Arctic. (ILLUSTRATION COURTESY CANWEST NEWS SERVICE)

This map shows the possible routes that early humans from Asia may have followed on their journey into North America. (ILLUSTRATION COURTESY CANWEST NEWS SERVICE)

RANDY BOSWELL

Canwest News Service

Two U.S. scientists have published a radical new theory about when, where and how humans migrated to the New World, arguing that the peopling of the Americas may have begun via Canada’s High Arctic islands and the Northwest Passage — much farther north and at least 10,000 years earlier than generally believed.

The hypothesis — described as “speculative” but “plausible” by the researchers themselves — appears in the latest issue of the journal Current Biology, which features a special series of new studies tracing humanity’s proliferation out of Africa and around the world beginning about 70,000 years ago.

The idea of an ancient Arctic migration as early as 25,000 years ago, proposed by University of Utah anthropologists Dennis O’Rourke and Jennifer Raff, would address several major gaps in prevailing theories about how the distant ancestors of today’s aboriginal people in North and South America arrived in the Western Hemisphere.

The most glaring of those gaps is the anomalous existence of a 14,500-year-old archeological site in Chile, near the southern extreme of the Americas, that clearly predates the time when East Asian hunters are thought to have first crossed from Siberia to Alaska via the Bering Land Bridge at the end of the last ice age some 13,000 years ago.

The new theory may also have implications for a lingering Canadian archeological mystery.

For decades, the Canadian Museum of Civilization has stood largely alone in defending its view that the Yukon’s Bluefish Caves hold evidence of a human presence in the Americas — tool flakes and butchered mammoth bones — going back about 20,000 years.

The Utah scientists, pointing to genetic affinities between certain central Asian populations and New World aboriginal groups, suggest an Arctic coastal migration may have begun from river outlets in present-day north-central Russia.

Using skin boats and hunting along glacier-free refuges while the last ice age was still underway, the prehistoric travellers could have moved quickly along the northern Siberian coast to northern Alaska, Canada’s Arctic Islands and beyond to eastern and southern parts of the Americas, they say.

“Movement to the interior of the continent via the Mackenzie River drainage,” the authors assert, “is plausible.”

And suspected gaps among Arctic glaciers means “open coastal areas for continued movement eastward would have provided access to the open water of Baffin Bay and Davis Strait and a coastal route along the eastern seaboard of North America,” the study states.

O’Rourke told Canwest News Service the theory doesn’t exclude existing models, but offers a new way of thinking about the movements of the earliest North Americans that deserves to be considered and “to be tested in rigorous ways.”

In recent years, the routes and timing of New World migration have been among the most contentious issues in science.

The Siberia-to-Alaska pathway for early hunter-gatherers, followed by a southward migration down a mid-continental “ice-free corridor” in present-day Northwest Territories and Alberta, is widely accepted and backed up by numerous archeological findings.

But a growing number of scientists, troubled by the age of the Chilean site and other wrinkles in the conventional migration story, have recently touted the likelihood of an earlier migration by seafaring people along the Pacific Coast.

However, purported coastal archeological sites that could yield traces of humans from 16,000 years ago or earlier are underwater today. Canadians scientists and others are probing potential sites in British Columbia and Alaska, but evidence remains extremely sketchy.

Equally puzzling is the fact that eastern North America has generated far more artifacts from the continent’s first known civilization, the Clovis people, than archeological sites in the West, where more relics would be expected.

Finally, DNA studies of current aboriginal populations — which can provide evidence of the geographic origins and migration patterns of ancient ancestors — have been at odds with the conventional migration models.

“As neither archeological nor genetic data have yet been able to unequivocally resolve many of the long-standing questions regarding American colonization, the generation of new models and hypotheses to which new and more powerful analyses may be applied is essential,” O’Rourke and Raff state in their paper.

In an interview, O’Rourke said the possibility of a very early northern migration is supported by recent research in Russia. In January 2004, a team of Russian scientists reported the remains of a 30,000-year-old human settlement near the Arctic Ocean outlet of Siberia’s Yana River, the most convincing evidence ever found for such an early, northerly human presence near the Bering gateway to the New World.

David Morrison, the Canadian Museum of Civilization’s director of archeology and an expert in Canada’s prehistoric Arctic peoples, applauded the U.S. researchers for floating a fairly “wild” theory because “that’s how science advances.”

But he said “count me skeptical” about the hypothesis, citing the “unspeakably harsh” conditions that the ancient Asians would have encountered in Canada’s Arctic before the full retreat of the glaciers.

“It was,” says Morrison, “a terrible environment.”

While he still thinks the Bluefish Caves predate the migration times in prevailing theories, he says such remote history is still only dimly understood pending the development of more comprehensive and credible scenarios.

“Going back 30,000 years requires you to speculate,” he says, “because we really don’t have much of an idea what was going on.”

But he added that Bluefish “has got to tie into the solution somehow.”

(0) Comments