Feature: From the tundra to the Korean War: Eddy Weetaltuk’s story

“I, Edward Weetaltuk, E9-422, was born in the snow…”

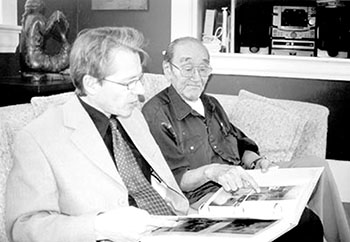

Thibault Martin, a professor at the Université de Quebec en Outaouais, looks at an album of photos with Eddy Weetaltuk when they worked together on his book in Winnipeg.(PHOTO PAR SYLVIANE LANTHIER)

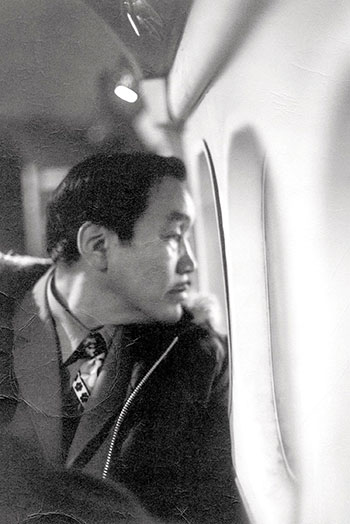

Weetaltuk looks out the window of a plane en route from Cape Dorset to Frobisher Bay.

THIBAULT MARTIN

Special to Nunatsiaq News

Eddy Weetaltuk returned to his home community of Kuujjuaraapik in 1967 after 15 years in the Canadian Forces — in 1974 he decided to write the story of his “adventures in the wide world.”

Over the course of a few months he wrote a manuscript of about 200 pages that he then sent to the Museum of Man (now the Museum of Civilization), asking the museum to publish it.

His request was never answered.

The manuscript would surface again 30 years later, when Weetaltuk took up his book project with the goal of writing “the first Inuit bestseller.”

Weetaltuk wanted to show young Inuit that education was important and that Inuit can become anything they want and even become famous, if that’s what they want.

That’s why Weetaltuk wanted his book to be published in several languages.

The French-language version is the first to be published because a publisher in Paris decided to make Weetaltuk’s story known to the greater public.

English-language publishers haven’t been as enthusiastic, but an English version will also be published in the near future.

Weetaltuk’s manuscript is an extraordinary document, mainly because it is the story of one of the first Canadian Inuit who decided to go to war, but also because he decided to write it by himself and by himself, back in 1974, without having been asked to by an anthropologist.

His manuscript is even more important because the story wasn’t written to answer anthropological questions or to pass on knowledge about traditions, which in itself is different from most the Inuit works.

In fact, his work is unique. It goes way beyond a simple autobiographical exercise and is more a work of literature.

It’s the story of the personal quest of a man who wants to forge his own destiny, and who, at the end of his journey, looks back on his life and the world he’s travelled. It offers an unflinching look— but never a harangue— against the western way of life.

Instead, it’s the questioning of a man who wanted to give sense to his life, to understand why he saw, the horrors of war and the joy that love can offer.

“I, Eddy Weetaltuk, E9-422, I was born in the snow while my mother cut wood to keep the family warm. My parents used to go to the Strutton Islands every spring to hunt belugas. That’s when I was born…”

That’s the introduction of the story of a man who travelled the world to escape the shackles of colonialism and, like white people, to feel free to know other cultures.

To do this, Weetaltuk had to hide his identity because when he was young, Inuit had been reduced to an Eskimo number. Their freedom of movement was also limited.

To chase his dream, Weetaltuk invented another name for himself, procured false identity papers, changed his E-number for an ID tag in the Canadian Armed Forces, and for nearly 20 years hid his Inuit background.

This “borrowed” life was the price Weetaltuk paid for being free.

But this freedom also carried heavy consequences. Weetaltuk couldn’t see his father before he died, he couldn’t marry his true love and, above all, living among white people, he felt that he was a traitor to his people.

When he realized he was losing himself, Weetaltuk decided to go back among his people where he started a new voyage, one that would bring his life full circle.

His story, which includes a message, never verges on a lecture. On the contrary, it is lighthearted, full of humour, people are intense, compelling, and filled with telling detail.

In 1974, Weetaltuk, the grandson of the famed George Weetaltuk, one of Robert Flaherty’s guides on “Nanook of the North” knew he had written an important document, but unfortunately no one in the world of writers and anthropologists agreed.

In this way, Weetaltuk shared the fate of many writers who were ahead of their time, but I am convinced that posterity will recognize him.

Eddy Weetaltuk died March 2, 2005, only a few days before the final version of his book was ready.

For more information, call or email Thibault Martin, who assisted with the editing and publication of this book: thibault.martin@uqo.ca; tel. 819-243-8240

E9-422

Un Inuit, de la toundra à la guerre de Corée

Editions Carnets Nord

382 pages

ISBN:9782355360251

(0) Comments