Inuit knowledge joins science in climate change study

Inuit observations on ice melt and storms help forecast global warming in the Arctic

GREG YOUNGER-LEWIS

Inuit hunters’ observations about changing weather patterns have helped scientists determine that global warming will strike hardest in the Arctic in the coming decades.

The Inuit Circumpolar Conference recently held a meeting in Iqaluit that gave a sneak preview of the report that merges scientific data with tradition indigenous knowledge on climate change.

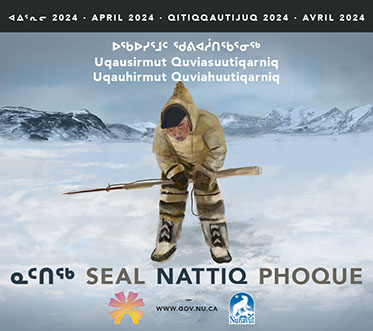

Authors predict rising temperatures will threaten Inuit and other indigenous people’s traditional hunting – and in turn, their culture – because climate change is reducing habitat for seal and polar bears, and altering caribou migration patterns.

Sheila Watt-Cloutier, chair of the ICC, said she expects the report, with accompanying policy recommendations, will give her group unprecedented leverage against the world’s biggest polluters, including the United States.

The U.S. and Russia remain the most significant hold-outs from the Kyoto Protocol, an international treaty on reducing greenhouse gas emissions created from burning coal, oil, and natural gas.

“This policy document is one that’s going to make effective change,” Watt-Cloutier said after the May 17 meeting in Iqaluit. “For the Arctic, [global warming] is not a theory. It’s happening today. It… has the potential to change our culture, our life.”

Over the past few years, authors of the report gathered stories from elders and hunters across the circumpolar North, and combined their comments with other scientific research.

The report, commissioned by the Arctic Council, an intergovernmental forum of the eight Arctic countries plus indigenous organizations, contains several key findings, including:

* annual Arctic temperatures have risen twice as fast as anywhere else on the planet over the past few decades;

* coastal communities face increasing exposure to storms;

* Arctic residents face higher exposure than ever to ultra-violet radiation, a component of sunlight know to cause skin cancer.

Jack Anawak, the federal government’s ambassador for circumpolar affairs, said he’s already seen the impact of global warming in Nunavut.

Anawak said hunting grounds are disappearing in certain areas, like Repulse Bay, where the ice floe was a third its normal size this winter.

He added that hunters can hardly travel between Cape Dorset and Repulse Bay anymore because the winter pack ice is thinning.

But Inuit are more prepared to adapt to the on-going weather and climate changes because they’ve become less dependent on hunting, Anawak said.

“I’m not sure exactly how Inuit can respond to a problem that’s not of our making,” he said in an interview during the meeting. “I think it’s a matter of adapting to the situation.”

The full report and policy recommendations will be presented to Arctic Council ministers in Iceland in November. The meeting will host representatives from Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the United States.

(0) Comments