Mining will drive double-digit economic growth in Nunavut this year: report

Conference Board of Canada offers bleak assessment of territory’s ability to train youth for mining careers

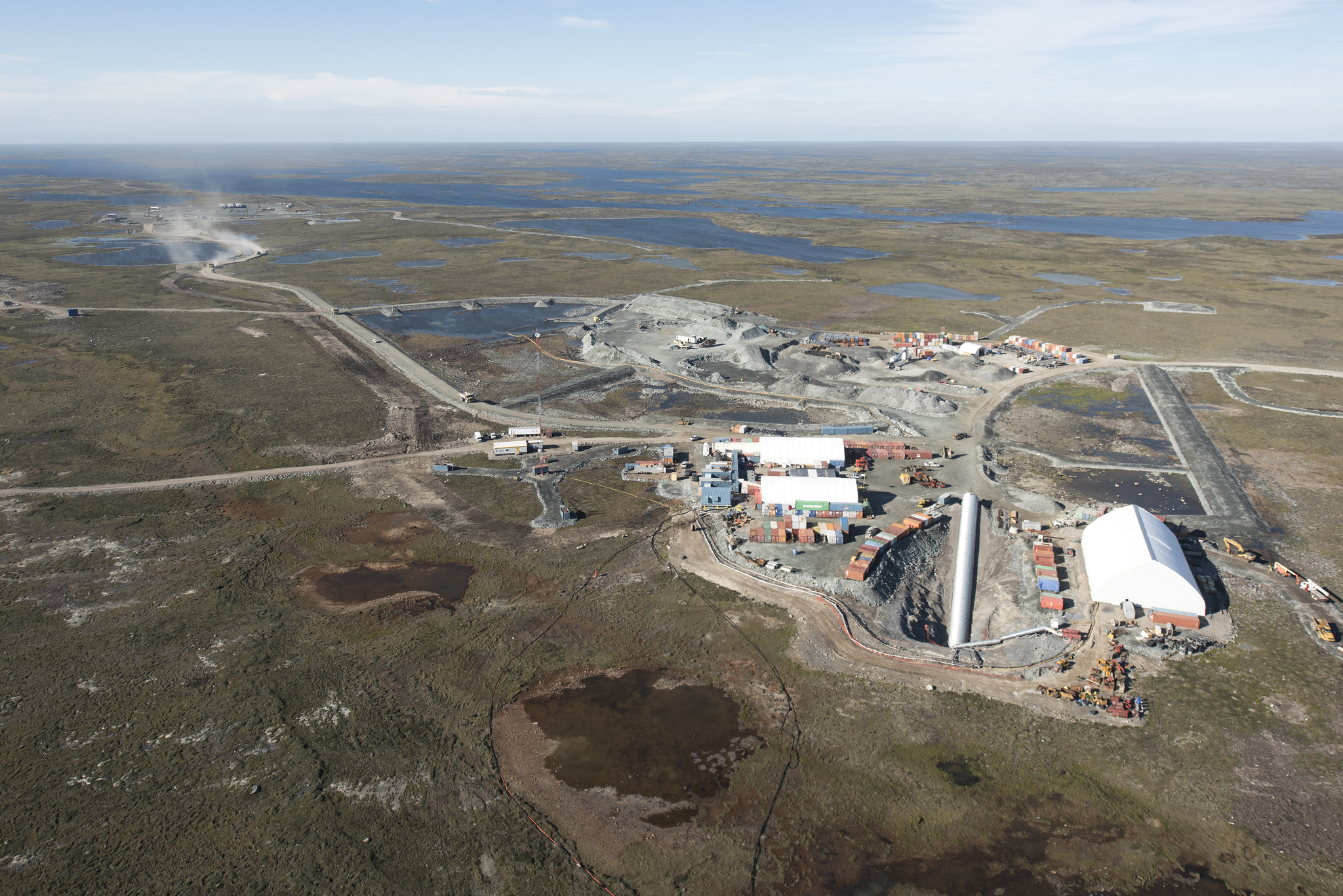

Agnico Eagle Mines Ltd.’s new Meliadine mine near Rankin Inlet recently began commercial production. Its operation will help Nunavut produce 1 million ounces of gold annually by 2022, according to a forecast by the Conference Board of Canada. (Photo courtesy of Agnico Eagle Mines Ltd./Flickr)

Nunavut’s mining boom will help the territory see enviable economic growth for the foreseeable future, according to a new forecast by the Conference Board of Canada.

But the report’s authors don’t expect this growth to make a big dent in the territory’s unemployment rate, which currently stands at nearly 2.5 times the national average.

“Most of the new jobs created in Nunavut’s mining industry will, unfortunately, go to non-residents as companies are forced to bring in workers from other parts of Canada due to a lack of specific mining skills within the resident population and to the remoteness of the mine sites,” the report states.

“Around one-third of the jobs created in Nunavut are typically filled by people who live in other parts of Canada and, consequently, are not counted in the territory’s job numbers. By 2025, the unemployment rate will drop to 12.7 per cent, down from current levels of close to 14 per cent, but will still be much higher than in the rest of the country.”

The report offers a bleak assessment of the territory’s ability to train its young residents to work in mining.

“Many of the young people in Nunavut today don’t have the skills needed to work in the mining industry, and they end up unemployed. Over the forecast, mining and construction companies will continue to bring in workers from other parts of Canada to meet their labour requirements.”

What new jobs will be found by Nunavut residents will likely involve transportation and retail, the report states. And, as it notes, “These jobs tend to pay less than jobs in mining.”

Nunavut’s high fertility rate poses another challenge in pulling down the unemployment rate.

“As women in Nunavut have more children, the labour force will grow much faster than in Yukon or the Northwest Territories,” the report states. “This will continue to put upward pressure on the unemployment rate, leaving many young people in Nunavut unable to find meaningful employment.”

Nunavut saw double-digit economic growth last year, and is similarly on track to see growth of 10.4 per cent this year.

As mine construction wraps up, that growth is expected to slow to 3 per cent by 2020, before picking up again over the medium term.

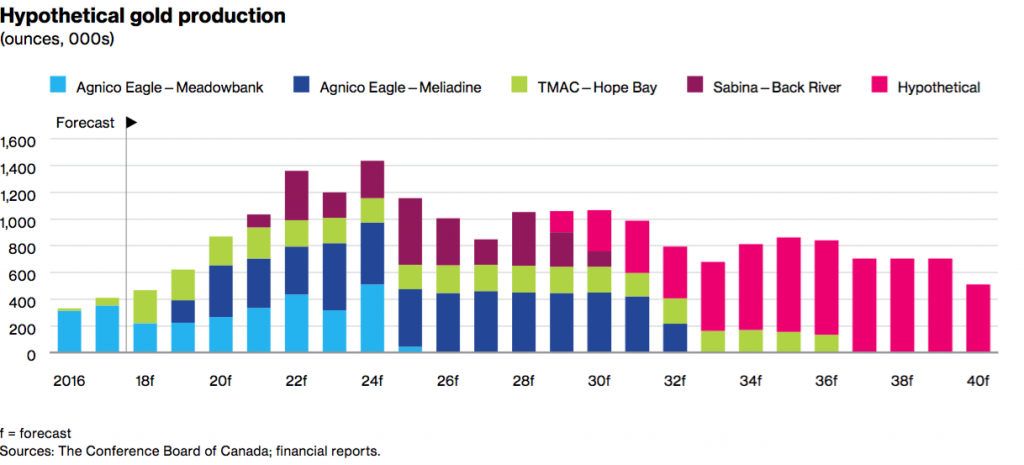

Nunavut produced 408,000 ounces of gold last year, from Agnico Eagle Mines Ltd.’s Meadowbank mine and TMAC Resources Inc.’s Hope Bay property. Gold production is forecast to more than double over the next two years, reaching 1 million ounces by 2022.

Agnico Eagle will be producing a lot of that gold. The company recently began commercial production at its new Meliadine mine near Rankin Inlet. And, as mining at Meadowbank winds down, Agnico Eagle plans to begin commercial production at its Amaruq satellite deposit later this year.

Gold production at TMAC Resources Inc.’s Hope Bay property in the Kitikmeot is also expected to be on the upswing. The company “had been experiencing capacity problems with its processing plant at Hope Bay, but the company now believes that these issues have been resolved,” the conference board’s report states.

Hope Bay produced 40,050 ounces of gold in the first quarter of 2019, and is expected to ramp up its annual production to about 200,000 ounces per year by 2020.

And TMAC envisions Hope Bay remaining in operation until 2036. That would make it the longest-operating mine in the territory.

Sabina’s Gold and Silver Corp.’s Back River mine in the Kitikmeot is also expected to begin producing gold sometime before the end of 2022. The conference board’s forecast anticipates Back River producing gold a year earlier than then, but that doesn’t reflect recent delays in financing that the company has encountered.

Nunavut’s economic prospects could be even brighter, if a number of mine projects end up coming on-stream that were excluded from the forecast.

For instance, while Baffinland Iron Mines Corp. shipped out 5.1 million tonnes of ore from its Mary River mine last year, the conference board isn’t yet banking on the company’s ambitious expansion plans to come to fruition.

A variety of concerns have been raised about the social and environmental impacts of the proposal, which would see a railroad built across Baffin Island, a big boost in ore production doubled to 12 million tonnes a year, and an extension of the shipping season.

The Nunavut Impact Review Board will hold final hearings on these plans in Pond Inlet and Iqaluit this autumn before it issues its recommendations.

Neither does the conference board include the plans of De Beers Group to build a diamond mine at its Chidliak property northeast of Iqaluit. More work needs to be done to establish the economic viability of the property, the report states. “Nonetheless, the project has some potential and could be brought into operation as soon as 2021.”

Nor does the conference board include MMG Resources Inc.’s dreams of unlocking the resource wealth along the Kitikmeot’s Izok Corridor. To do so, the company is hoping that governments will build an all-weather port and road for it.

So far, territorial and federal governments haven’t shown interest, although the Kitikmeot Inuit Association re-applied for federal funding for the project in April.

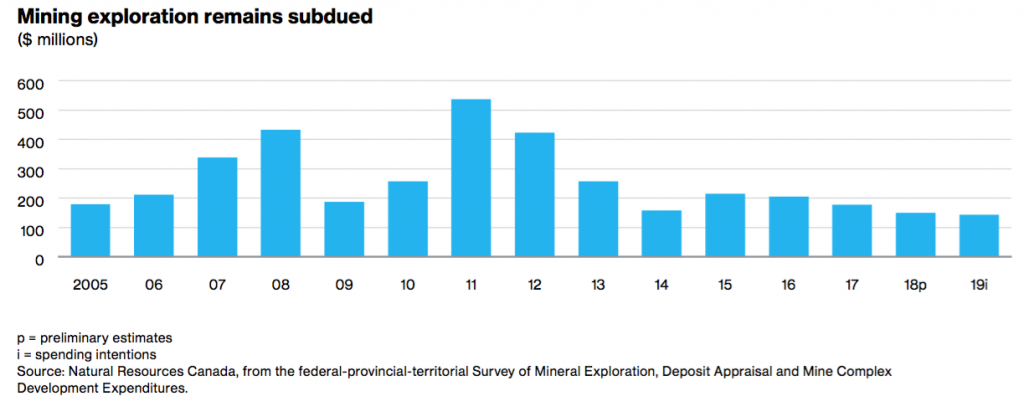

The conference board found it “somewhat surprising” that, at a time when gold prices were rising, the amount spent on mineral exploration in Nunavut slumped in 2018 to $149.6 million, down from 177 million in 2017. An additional drop to $144.3 million is expected in 2019.

“While Nunavut is home to several promising projects, a lack of infrastructure makes it more difficult to develop new mines there than in other parts of Canada,” the report states.

The conference board says that Nunavut’s growing numbers of elderly residents and youth will create demand for increasing spending on health care and education. Currently, these categories eat up one-third of the territorial government’s revenues, and that share is set to grow to 38 per cent by 2030.

But increased revenues from mining should mean the territory is able to keep pace with this higher spending.

As well, the conference board envisions a slowdown in the outflow of people to other parts of Canada. That’s important, because more residents means more generous transfers from Ottawa.

These transfer payments currently make up nearly 90 per cent of the territory’s revenues.

We Nunavummiut are given a bleak futuristic outcome. We have a broken education system where youth are put from one grade to the next based on age, not on ability and in Grade 10, made to face real education and thusly fail. This has effectively made Nunavut youth ineligible to be part of Canada’s wage economy and made to live on welfare while “educated” transients come up and take over the jobs available. Let us Nunavummiut abolish social passing and have a proper education system that will be meaningful in assisting our youth in getting employment opportunities.

How much revenue does the GN actually get out of mining? Isn’t all the royalties going to IRAs and NTI?

Other then the Payroll tax, how much of this revenue is actually going towards GNs budget? If all the royalties are going to NTI and IRAs shouldn’t they be using those funds to create more housing, improve education so youth can get jobs, and improve health care in the territory?

Focusing on royalties is a bit of a red herring. Sure, a mine may generate a few million in royalties, but money paid directly to employees usually dwarfs it. For instance, in 2017 Agnico-Eagle’s Inuit employees were paid $19.4 million in wages. $511 million went to Nunavut-based businesses (although, of course, most of that would flow south to buy the things the contractors are supplying the mines). The amount of royalties was far less than that.

The GN receives payroll, property, and (and now again) fuel taxes from operating mines in Nunavut. The GN also benefits from mine employment as social payments spent to support previously destitute people are reduced. Although the amount of financial benefits to the GN may be low and some indirect, they exist.

Whether or not GN receives money from an industry is not a reason determining whether or not that industry should take over GN’s job. The GN is a duly constituted level of government that has been made responsible for all the issues you list by the Parliament of Canada. Mining or any other kind of business has not. Same for Inuit organizations.

Here is a thought. What does the GN receive from the Arts and Crafts, Tourism and Fishing industries? Answer: next to nothing, and certainly no “royalties” of any kind. Should not then a cruise ship company, the Nunavut Fisheries Coalition, or an art gallery be made responsible for putting a roof over your head, or building health centers?

The absence of financial benefit from these sectors has not stopped GN from supporting them to the hilt – through countless training programs, wages subsidies, research and regulatory support, marketing funding, creating territorial crown corporations etc. Non-stop since Nunavut was created. There has been very little growth to show for this, and the potential for these sectors alone to make us self sufficient is ZERO. Why is one sector not treated the same as any other?

I think part of the reason is this – our own government is discriminating against us, based on an out-dated construct of Inuit society and culture perceived by southern hired senior management. They are picking and choosing which industries they think are appropriate for Inuit to have and participate in, ignoring all the compelling economic arguments (above).

Regional Inuit Organizations are responsible for the Inuit Impact Benefit Agreements. They should require training for Inuit.

All three pretty much require training as part of the IIBAs. The problem is they can’t cover the entire Nunavut educational system, which is terrible.

Yes the Regional Inuit Organizations require training as part of the IIBAs. But is it the right training?

Inuit need a plan to get the training necessary so that the next gold mine, or at least the one after that, can be 100% owned by Inuit and staffed entirely by Inuit. That is the objective and we need a plan to get there. If the plan does not get us there, it’s the wrong plan.

That…is optimistic. A nice goal, but it’s not going to be the next mine, not unless there’s a hidden group of Inuit mine geologists, engineers, process plant workers, surveyors, mine-planners, accountants, financial and market experts, business lawyers, biologists, all with years and years of experience in the industry, that no one knows about.

A province with the population and resources of an Ontario would find it almost impossible to staff with only Ontarians, let alone Ontarians of only one ethnic group.

To expect to be able to do it in Nunavut, even if it were a laudable goal, (which it isn’t imho), is, as said above, very optimistic.

Mon premier entretien d’embauche avec Agnico Mines a eu lieu l’an dernier pour Data Entry Clerk. Je répondais à leur question et disais que je connaissais bien les responsabilités du poste, puis ils posaient une question sur l’emplacement (Mirabel) du poste qu’ils annoncaient. J’ai dit, j’ai mon permis de conduire qui est validé. Ensuite, on m’a dit que je ne pouvais pas gérer les trajets quotidiens. Et ces Inuit ne savent pas conduire et sont responsables de leur poste. Ensuite, ils m’ont posé des questions en français auxquelles j’ai répondu et répondu à leurs questions. Ensuite, ils ont dit que les Inuit ne parlaient pas français.