New book explores history of ‘dehumanizing’ Eskimo disc system

Author Norma Dunning weaves family and Inuit history in ‘Kinauvit? What’s Your Name?’

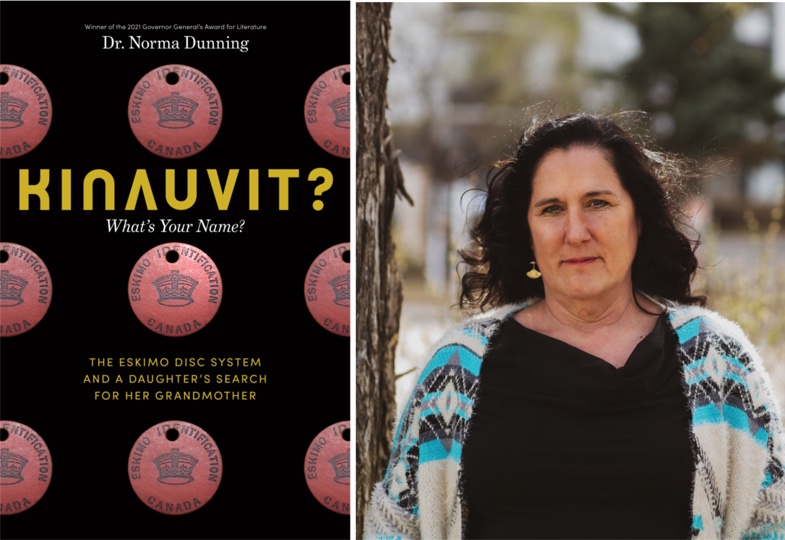

Inuk author and scholar Norma Dunning’s latest book “Kinauvit? What’s Your Name? The Eskimo Disc System and a Daughter’s Search for her Grandmother” looks at the mostly unknown history of the federal government’s disc system that was used in the early twentieth century to keep track of Inuit in the Arctic. (Photos courtesy of Douglas & McIntyre / Harbour Publishing)

When author Norma Dunning began the process of applying to be a beneficiary under the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement about twenty years ago, she was asked a curious question in her application:

What was her disc number?

It was a question that prompted Dunning, a writer and academic in Edmonton, to explore the history of a government identification system for Inuit and her own identity as an Inuk.

The identification disc system began in 1941 as a way for the federal government to keep track of Inuit in the North, Dunning explained.

The idea was every Inuk would be assigned an official documentation number on a small disc, which they would wear around their neck or sew into their clothing.

Part history book and part memoir, Kinauvit? What’s Your Name? The Eskimo Disc System and a Daughter’s Search for her Grandmother compiles years of Dunning’s research into the then-called “Eskimo Identification Tag System,” interviews she did with elders and her own personal story growing up with a complicated sense of cultural identity.

“Nobody’s ever really sat down and put together the history,” she said in an interview. “I hope people walk away informed.”

Despite being in place for three decades — from 1941 until the early 1970s — there was little information about it when Dunning began her research, she said.

Dunning searched through library archives to find what she could about how and why the system was implemented.

“It’s a really convoluted system to try to find information on — there’s little bits and pieces here or there,” she said.

Essentially, it was a dehumanizing method for the government to control Inuit, Dunning said.

“Every every aspect of Inuit life was under surveillance. You could not do any kind of commerce, you couldn’t go to the doctor, you couldn’t go to school unless you had that number,” she said.

“I’ve had people say to me, ‘well, we all have numbers, like driver license numbers’, but we don’t have to memorize them or tell the clerk at Safeway, when I’m buying my groceries, my number.”

At the same time that the system was designed to keep tabs on Inuit, it also showed a lack of cultural awareness by its creators.

Dunning found evidence that, at one point during the discussion about what the disc should look like, government officials were considering engraving the image of a bison, an animal that doesn’t even live in the Arctic and isn’t a part of Inuit culture.

“It is ridiculous and it shows ignorance of the people at that time who were in the North and were the ones administering the system,” Dunning said.

Information about the tag system that Dunning couldn’t find in archival materials, she found instead through hours of interviews with Inuit community members who experienced the tag system firsthand, or who had relatives who had been given a number.

In turn, those conversations helped Dunning reflect on her own Inuit identity and upbringing.

The book actually began as Dunning’s master’s thesis, a straightfoward academic text with none of the personal elements that are now woven into the book. Then Dunning’s editor encouraged her to include herself in the story.

It opens with a scene from Dunning’s own childhood growing up in Quebec, when she asks her mother in the kitchen what their family is. Her mother tells her that they are French, a story that Dunning repeats throughout her life, but knowing deep down that there is more to her family’s story than her mother will let her know.

“I think that we spend our entire lives trying to sort out what our identity is,” Dunning said.

It wasn’t until Dunning was an adult that she began to connect the dots of her family’s Inuit history, taking the first steps to enroll herself and her sons as beneficiaries and opening up the door for them to proudly identify as Inuit too.

“I don’t think that my story is so unusual. I think that there’s many Indigenous children who are not told exactly what they are. I think it’s how the world has become and how especially Indigenous mothers protect their children.”

Dunning hopes more awareness of the disc identification system will lead to more accountability from governments.

“When we have a system that is silenced and hushed in our country for decade upon decade upon decade, I do think that an apology is necessary. It’s about acknowledgement and accountability,” she said.

Kinauvit? What’s Your Name? The Eskimo Disc System and a Daughter’s Search for her Grandmother is available now in bookstores and online through Douglas & McIntyre Press.

Back in 1973, I had a work assignment for the NWT Dept. of Social Services that had me correlating records from school, social services, housing, and medical files (privacy laws would probably ban that today). Only the hospital regularly used the disk numbers, and only the disk numbers were consistently accurate. In other departments, there were variations in spelling of a person’s name, differences in the name itself (traditional Inuktitut, baptismal, English nick-name; surname traditionally used by a person or his family, surname chosen a few years earlier during Project Surname, something else entirely.)

As I said, this was in 1973, less than 10 years after I’d been gifted with a 9-digit SIN. It’s hard to be shocked by disc numbers.

Very interesting story. There are probably many stories out there regarding the disk system. Only in my late fifties did I learn that I was photographed as a child facing forward with my number, then photographed facing sideways again with my number. Just like how criminals are identified with their numbers. To this day that number is engrained in my memory. I still have the photo of me facing forward with my number. I am sure many Inuit were photographed without their knowledge.

I was photographed for my driver license last year and i felt the same way, like they must have saw me as criminal. Same with my passport too.

To this day I still have my government-imposed social insurance number engrained in my memory.

My letters from Revenue Canada for taxes still use my disc # under my name as…otherwise known as E8….when my disc # was issued to a totally different name, gender was wrong and only date of birth was correct.

Is this the same Dunning that Nunatsiaq once fawned over as an authoritative voice on the name of the ‘Edmonton Eskimos’? If you can dig back and find that thread, it’s well worth a read.

The idea that these numbers were used for surveillance is a good example of a person imposing a view from the present, where tech makes this a possibility, onto an age where information gathered would render little more than a useless blurr of pixelated data.

This is the problem I see with too many journalists, they are so easily seduced by the imaginings of people whose credibility as a career ‘thinker’ depends almost entirely on the strength of their imagination.

Is there evidence to substantiate these claims (maybe in the book?) Or, do we prostrate before made up authority based on identity and title alone? Apparently…

i’ll read the book but this article has me unconvinced. more “evil government”. how terrible that they gave identification to people in a form meant to survive the harsh lifestyle. like some other articles this week about genocide i suppose this was our federal government emulating the nazis right?

I’m surprised there was no comparison made to the ‘Jewish badge’ of the Holocaust. Perhaps in time we will arrive there.

Given that the discs were developed in the early stages of the Second World War, they were undoubtedly modeled around military practice, thus the name ‘dog tags.’

Still, to say this was dehumanizing is to offer an interpretation. People who are committed to this kind of frame are committed, in my opinion, chose ‘marginalization’ as a foundation of their identity; one they wish to spread with the zeal of evangelicals.

I think the Nazi’s came to Canada to check out the Canadian residential schools for natives, and then the Nazi’s made concentration camps.

The idea came from the second Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902

Nope, the consensus opinion is pretty clear that concentration camps as we understand them go back to the Brits and the Boer War.

I’m not sure about the Nazis, but I do know South Africa came to study the reservation system when establishing apartheid.

(Sigh)… another one attempting to get fame and fortune…

So should they have been given a card to put in their wallets? Did they carry wallets around in their nomadic lifestyles 80 years ago? They got rid of the discs once people moved into communities.

I’ve never heard a convincing argument for how else the government would have kept records on people for things like health care and vaccinations, so that people got the proper treatment – if they hadn’t and had given the wrong vaccinations or treatments to the wrong person in an attempt to not “depersonalize” with a number, then that would be an outrageous scandal.

Let’s not forget too that people would change their names, had no surnames, and written language was not well developed and used syllabics, when the people offering the services were english and french speaker for the most part. To offer correct services, you need to be able to be sure that you have the right person.

When an academic has only a thin connection to a ‘marginalized’ group, and they see the career benefits of amplifying that connection to enjoy a certain clout, the incentive structure can clearly lead to the production (some might say performance) of exaggerated, mystical realities.

Move on, reconcile. There’s a wide open road ahead, just like driving a vehicle small rear view mirror and big windshield. Quit dwelling in the past.

Exactly!!

Amen.

What was the name of Norma’s thesis? I am interested in locating and reading that.

Does anyone have a link to that piece of Academia?

When my father and uncles joined the forces, they were FORCED to have a military number,

and we’re FORCED TO WEAR AN I. D. DISC with there number on it.

Today we are FORCED to have a S.I.N. #.

We should all be compensated for this and all people given a formal apology.

Nothing against FIRST NATIONS OR INUIT PEOPLE at all , who complain about things, but

other Canadians have the right to complain same as any one else

Not surprising all the negative comments on here are by people not at all related to anyone who had disc numbers. Not surprising at all. Sad in fact, that it is so difficult for you to understand that these numbers had to be on your person at all times. You were not referred by your name, but by your number, and one of the reasons why they came up with the tag system was because Inuit names were too difficult for their frail tongues to pronounce. Yes, Canada has a very very dark history. Look up communications between government agents in settlements corresponding with Ottawa on the issue of Eskimos. If those communications don’t make you nauseous, you are not human. All I’m reading in the above comments is a bunch of ignorance. You are a bunch of ingnorants.

What I notice from people like “ever notice” is that after taking few shots at people who challenge a position on grounds that it appeals to emotion and not fact, they continue to appeal to emotion and not fact. How about you say something convincing? How about you refer to these government sources? How about your elaborate on this dark dark history? Truth and reconciliation requires truth first. Not these overinflated and oversimplified (apparently not simple enough for some institutions for a thesis) antics of victimhood.

The Alexander Stevenson fonds housed at the Nunavut Archives has some interesting files on the disc system. Some very candid files in this collection, which are worth checking out if you have the time/interest. According to some of the files, discs were issued because many Inuit had the same first name. This is still true today and this is attributed to the naming/namesake practices that we still practice, where a deceased loved one lives on in name through children. We can have many children named after one deceased person. Many children have more than one name, and in the colonial era in the Arctic, the “quiet invasion” of southerners who wanted to show Arctic sovereignty by way of government administration, the discs were used as a way to differentiate between the names (at least according to the Stevenson fonds). This ensured that when they arrested Inuit for criminal charges (again to show the world Arctic sovereignty), they had the right person. In some cases, the Northwest Mounted Police files, as well, note how many Inuit with the same name and concern to document that witnesses and interpreters who had the same name as the accused were differentiated in the records.