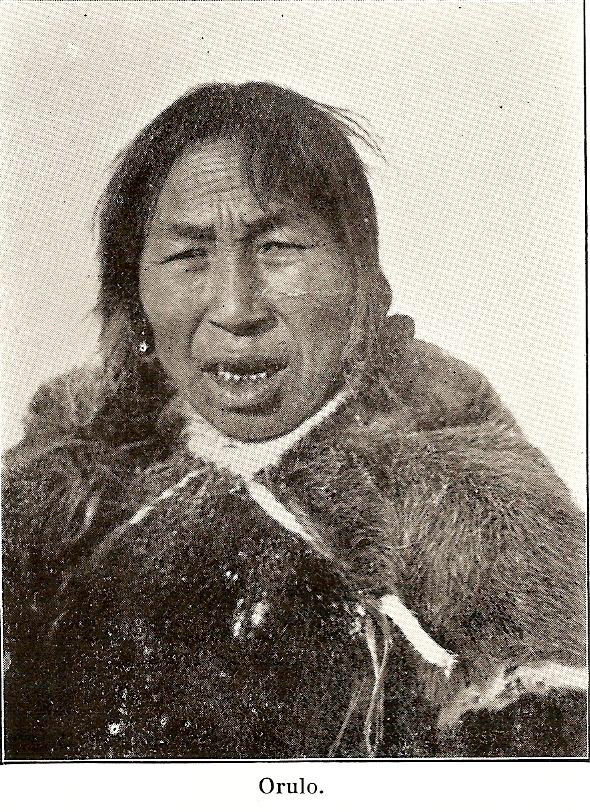

Orulo, wife of the shaman Aua. (Source: The Intellectual Culture of the Iglulik Eskimo. (Report of the Fifth Thule Expedition, Vol. VII, No. 1, facing page 49.)

Orulo – ‘To think I had been so happy’

A story from the Fifth Thule Expedition

Knud Rasmussen learned much about shamanism and Inuit life from Aua, an old man whom he met in 1922 on Melville Peninsula during the Fifth Thule Expedition.

But on Rasmussen’s visits to the patriarch’s camp, he also met the shaman’s wife, Orulo, and recorded the events of her life as she herself recounted them.

Orulo had endured tremendous hardship, punctuated by periods of extreme happiness and joy. She told Rasmussen stories, not of shamanism, but legends, observations, and the details of her own life.

She told of her birth in the farthest northern reaches of Baffin Island:

“I am called Orulo (“the difficult one”), but my name is really Aqiggiarjuk (“the little ptarmigan”). I was born at the mouth of Admiralty Inlet. While I was still a little child carried on my mother’s back, my parents left Baffin Land and settled at Iglulik.”

She described her childhood, the restrictions placed on her mother by a slavish adherence to taboo when she endured the birth of another child, and a subsequent move to Piling on the central west coast of Baffin. She told of the death of a beloved little brother and then of her father:

“I remember he was tied up in a skin and dragged away from the village, and left lying out in the open with his face turned towards the west. My mother told me that was because he was an old man, and such must always be set to face the quarter whence the dark of night comes, children to face the morning, and young people towards the spot where the sun is seen at noon.”

She learned about death from that experience: “That was the first time I learned that people were afraid of the dead, and had special customs on that account. But I was not afraid of father, who had always been kind to me. And I thought it was hard that he should lie all uncovered out in the open like that. But mother explained that I must thence-forward never think of my father in the body. His soul was already in the land of the dead, and he would feel no more pain there.”

Rasmussen listed attentively as the old lady told legends and explained Inuit beliefs. Then he began to question her about inconsistencies in her stories. “I could not understand,” he wrote, by way of example, “where the seals came from that lived in the sea long before the Mother of the Sea Beasts ever existed.”

But Orulo only laughed. Rather than try to explain the inexplicable, she brushed the questions off with an observation:

“Too much thought only leads to trouble. All this that we are talking about now happened in a time so far back that there was no time at all. We Eskimos do not concern ourselves with solving all riddles. We repeat the old stories in the way they were told to us and with the words we ourselves remember. And if there should then seem to be a lack of reason in the story as a whole, there is yet enough remaining in the way of incomprehensible happenings, which our thought cannot grasp. If it were but everyday ordinary things, there would be nothing to believe in.”

She referred to Aua by the pet name of Uvitaara (“my new husband”). She described her marriage as “the end of all my adventures,” adding that “one who lives happily has no adventures, and in truth, I have lived happily and had seven children.”

Rasmussen asked the woman, “What is the bitterest memory of all you can remember?”

Without hesitation, she answered, “The bitterest I have ever known was a time of famine shortly after my eldest son was born. And to make matters worse, all our stores of meat from the previous hunting had been destroyed by wolverines. During the two coldest months of the winter, Uvitaara hardly slept indoors a single night, but was out all the time hunting seal, and made do with a snatch of sleep now and then in the little snow shelters he built by the blow holes. We nearly starved to death, for in all that time he got only two seals. To see him go out, cold and hungry day after day to his hunting, in all manner of cruel weather, to see him grow thinner and weaker all the time — oh, it was terrible. But then at last he got a walrus, and we were saved.”

Rasmussen then asked the obvious question, “And the happiest thing you can remember?”

The old woman broke into a broad smile and put down her sewing, as she recalled a time long ago. “It was the first time I came back to Baffin Land after I was married,” she began. “I had always been a poor fatherless creature, passed from hand to hand; but now I was welcomed with great festivity by all in the village. My husband had come to challenge one of the others to a song contest, and there were many feasts on that occasion, feasts such I had only heard about, but never taken part in myself.”

When she had finished sharing her memories, Orulo suddenly burst into tears. But they were tears of joy.

She explained to Rasmussen, “I have today been a child once more. While I was telling you all about my life, I lived it over again, and saw and felt everything in the same way as when it really happened. There are so many things we do not think of until the memories are upon us. And now you have learned the life of an old woman from the very beginning to this day. And I could not help crying for joy to think I had been so happy…”

Taissumani is an occasional column that recalls events of historical interest. Kenn Harper is a historian and writer who lived in the Arctic for over 50 years. He is the author of “Minik: the New York Eskimo” and “Thou Shalt Do No Murder,” among other books. Feedback? Send your comments and questions to kennharper@hotmail.com.

Thanks again for sharing Mr. Harper.

I took your advice and read Across Arctic America, Kenn. It was eye opening, and thankfully not over concerned with niceties. Great read, I especially appreciate the peak into the lives of the shamans.

Thank you for the recommend.

Very interesting reading of history in the eyes of the Inuit.

Thank you for sharing.

I intend to

search for the book referenced by the previous writer.

Interesting to read of history, koana for sharing. I, myself googled The Canadian Expedition & came across the book “The Copper Eskimos’. Had I not found this, I would still be wondering if I will ever see a picture of my grandfather, he was shaman. My late mother never had any pictures of her father, only to explain that her older half brother looks like him. Stories like these are interesting, how our ancestors survive & places they travel, When I read stories and/or diaries of past explorers, I tend to see/live through their travels.

This was a great read! Thank you for sharing.

Hi Kenn,

I had read a couple of the books about the 5th Thule Expedition while camping last spring. I actually read “Across Arctic America” out loud to my mom and step-father nightly at the cabin. Then I read the “Intellectual Culture of the Iglulik Eskimos” on my own in my tent that same spring.

What I found interesting was that there were very nice drawings by my great grandmother (and the person I am named after), Pakak. But I did not see any mention of her in Knud’s writing, just her drawings. I would have loved to hear more about her, or even her husband Arrak Qulittalik.

I haven’t read the other “intellectual culture” books of the other groups yet (like the netsilik and such), could they be mentioned in one of those?

Thank you

Any recommendations on “Copper Inuit” are most welcome.

Tuharnaarnaqhivaktut taigualiugatit, quana.

I have Diamond Jenness’ book ‘The Life of the Copper Eskimo’ (1922) on order, it looks like it might be a good one.

One of the best ones, Kenn!

You and Rasmussen stick closely to the style of narrative that is very Inuit; you let the source tell the story as you draw out the important details.

Very soothing story Ken, Arnakak family Is the one I have been trying to find t since October. Pat Okoakuluk, Archie and family. I just wanted to say and let you know how thankful I am to know good people like you. Since October my thoughts have been with all of you and will be for awhile. For so many years Mike, you have been with us all the way for more than half of your life. Your respect to us Inuit will never be forgotten. Even we are not living in Iqaluit, we have missed you so much. With little respect to each other we are learning little by little. I remember you were teaching that to us. And, I am so proud of PJ. He was the one who gave us help even though we are not living in Iqaluit. I wish you all the best for the year in 2022.

Excerpt: Often the wizard will remain away for some time, and in that case, the guests will entertain themselves meanwhile by singing old songs, but keep their eyes closed all the time. It is said that there is great rejoicing in the Land of Day when a wizard comes on a visit. The people come rushing out of their houses all at once; but the houses have no doors for going in or out, the souls just pass through the walls where they please, or through the roof, coming out without even making a hole. And though they can be seen, yet they as if made of nothing. They hurry towards the newcomer, glad to greet him and make him welcome, thinking that it is the soul of a dead man that comes, and one of themselves. But when he says “Putdlaliuvunga” (I am still creature of the flesh) they turn sorrowfully away.

He stays there awhile, and then returns to earth where his fellows are waiting for him, and tells of all he has seen.