Arctic ice extent is unlikely to hit a record-low minimum, but lingering ice is ‘thin and porous’

Researchers are surprised by the low quality of sea ice in the Arctic.

Sea ice photographed from the research icebreaker RV Polarstern as it approached the North Pole was covered with melt ponds, melting from the bottom and was easy for the ship to sail through. (Folke Mehrtens / AWI)

Ice is still present in the Arctic Ocean, and a record-low minimum extent is highly unlikely next month, experts say.

But the low quality of the sea ice floating in the Arctic has been startling, they say.

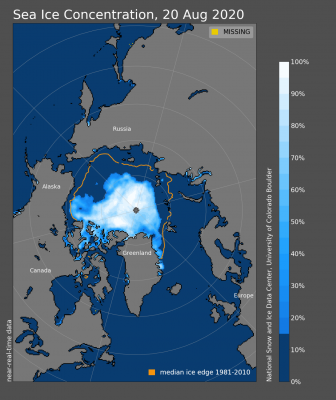

Sea ice extent is defined as areas where there is at least 15 percent ice cover—sufficient to show up in satellite imagery—and concentrations are low in places that used to have solid and thick freeze.

That was the case north of Greenland when the Polarstern, the icebreaker carrying scientists on the year-long MOSAiC expedition in the Arctic, was reaching the North Pole.

The Polarstern encountered stretches of open water most of the way to the pole and were “surprised to see how soft and easy to traverse the ice up to 88 degrees North is this year, having thawed to the point of being thin and porous,” said the ship’s captain, Thomas Wunderlich.

It was also the case on the other side of the Arctic, where large holes had developed by mid-August in the low-concentration ice in the Chukchi and Beaufort seas, according to National Snow and Ice Data Center.

Extent as of mid-August was running at the third-lowest level for this time of year, the Colorado-based center reported. That put it in an approximate tie with mid-August ice extent for 2007. September of 2007 wound up posting what was at the time a record-low minimum.

A map from the National Snow and Ice Data Center shows sea ice concentrations on August 20, 2020. While most researchers don’t forecast a new record low sea ice extent this year, concentrations show a trend of diminishing ice continues. (NSIDC)

Earlier this summer, Arctic ice extent was trending at or near record low levels—thanks in large part to extreme heat in the Siberian part of the Arctic that dramatically expanded areas of open water. The loss in ice extent slowed in July before picking up in recent days.

This late in the summer, with the autumn equinox approaching, the majority of the melt is no longer from the sunlight above, said NSIDC Director Mark Serreze.

“It’s mostly bottom melt at this point,” he said. “The ocean’s built up a lot of heat by this time of year.”

Serreze believes this year’s minimum extent is headed to a point like that of 2007, which at the time was a record-low extent. While 2012 remains, by far, the record low, 2007 is one of several years clustered in near-ties at the second-lowest or third-lowest spot.

Other experts have made similar predictions. Among the 38 projections submitted to the Sea Ice Prediction Network, only two predicted a record-low September extent. The median July outlook was for an average September extent of 4.36 million square kilometers, similar to the average extent last year and in 2007.

Just how much longer there will be summer sea ice at all is a matter of debate.

A new study, using models that hearken back to the last interglacial period 116,000 to 130,000 years ago, projects an ice-free Arctic Ocean could arrive as early as 2035. The study, published in the journal Nature Climate Change, examines the role of melt ponds that emerge as the sun sends heat in the spring.

“By understanding what happened during Earth’s last warm period we are in a better position to understand what will happen in the future. The prospect of loss of sea-ice by 2035 should really be focussing all our minds on achieving a low-carbon world as soon as humanly feasible,” the study’s joint lead author, Louise Sime of the British Antarctic Society, said in a statement.

Serreze, who has been on the record in the past forecasting a possible ice-free Arctic by the 2030s, now believes that threshold will arrive a little later than that.

“It seems the ice is a little more resilient than we had thought,” he said. “It’s just going down, but it’s not falling over a cliff.”

The threshold looks more likely to come in the 2040s, he said. That is not too far into the future, he said. “I may still be alive then,” he said.

Similar questions are now posed about the duration of the Greenland ice sheet, which is also monitored by the NSIDC.

A new study found that Greenland last year set a new record for annual mass loss, at 532 gigatons for the full year and 223 gigatons for the month of July alone. The study, published Thursday in the journal Communications Earth & Environment, relies on measurements taken by satellite. Despite a lot of year-to-year variabilities, it said, the Greenland ice sheet “has remained on a trajectory of increasing mass loss since the late 1990s in response to Arctic warming.”

[Greenland’s ice sheet saw record mass loss in 2019, study finds]

Greenland’s ice melt has accelerated so much that future mass loss is assured, even if surface melt declines, said a different study published a week earlier in the same journal and by some of the same authors. Dramatic flow from Greenland’s outlet glaciers is driving the decline; widespread glacial retreat is “sufficient to effectively shift the ice sheet to a state of persistent mass loss,” offsetting any replenishment from winter snows, the study said.

This year, Greenland ice sheet melt has been well above the long-term average measured in the satellite era but not as extreme as in a few recent years, the NSIDC reported.

Greenland’s melt has global consequences.

At current rates of carbon emissions, the Greenland ice sheet will contribute 10 centimetres of 12.6 centimetres to global sea levels by the end of the century, according to another study, published in the International Journal of Climatology. The study found that from 1991 to 2019, air temperatures in coastal Greenland have increased by 4.4 degrees Celsius in winter and 1.7 degrees C in summer.

This article originally appeared at Arctic Today and is republished with permission.

(0) Comments