Akumalik—an Inuit religious leader

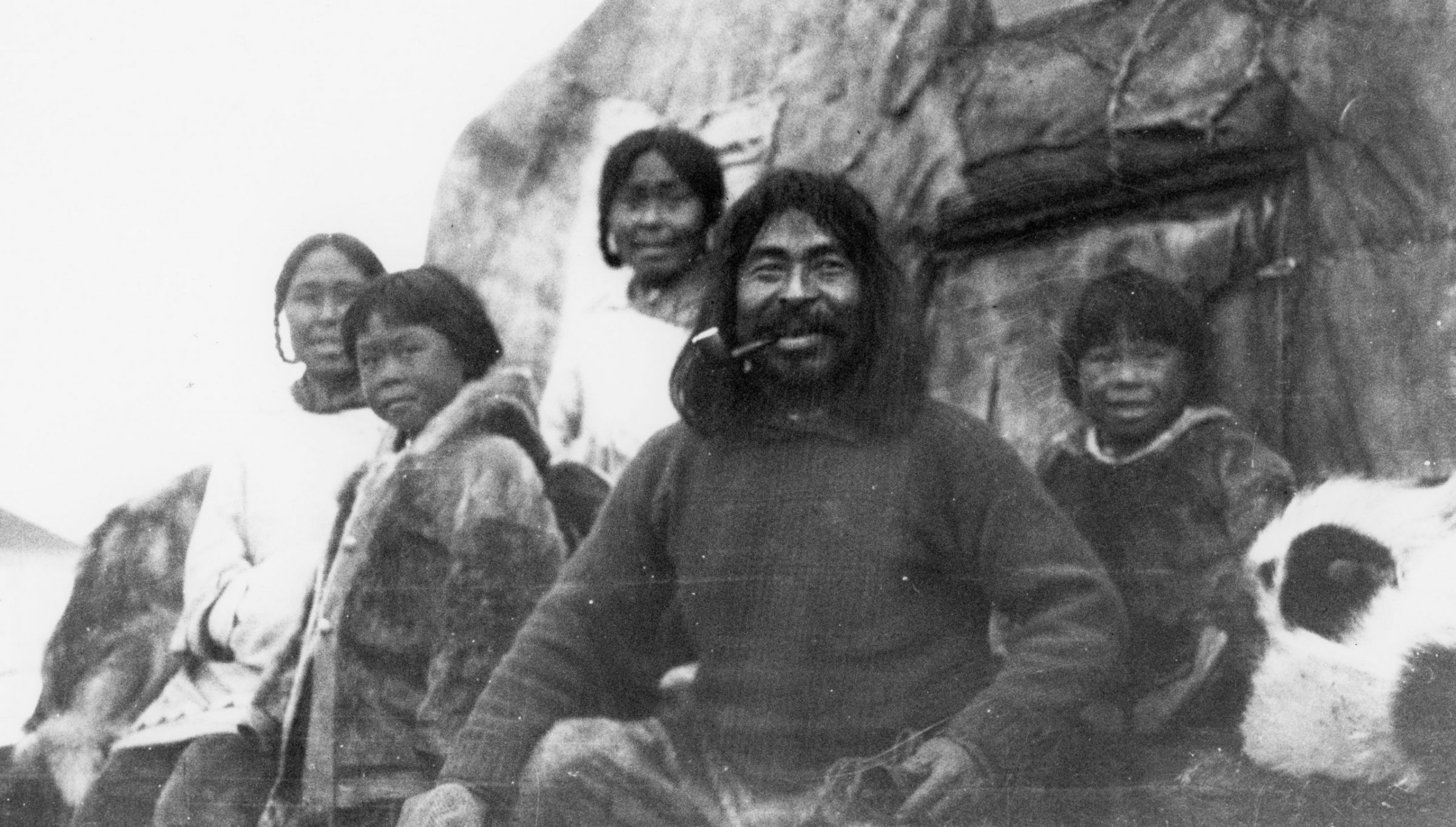

Akumalik (centre) and his wife, Arnaujaq, on the far left, with their son Illauq (Idlout) beside her in 1923. (Photo from Kenn Harper’s collection)

A rudimentary knowledge of a new religion, Christianity, reached northern Baffin Island in 1903, when a group of Cumberland Sound Inuit accompanied the whalers James Mutch and William Duval to the area.

They spent their first year at Erik Harbour before Mutch relocated his vessel to Albert Harbour, which he named for his ship. The Uqqurmiut who moved from southeast Baffin to Pond Inlet left no written records of the move or their experiences, but a missionary who had served at Blacklead Island in Cumberland Sound made a maddeningly brief reference to the event the following year.

He wrote about one convert to Christianity from his mission, “a poor lame girl, [who] has gone far away to the north of us with her family, the man being employed at a new whaling station. Here the Eskimo are in the darkest of heathenism, but this poor girl has taken Gospels, portions of other Scriptures, and other books with her, and has promised to teach what she can, and do all she is able for her Master’s sake.”

The young woman’s efforts are not known to have left any lasting results in the region. Inuit may have heard of the religion of the Qallunaat even earlier, from whalers, and they would also soon experience religious services on the Arctic, Captain Bernier’s ship which wintered at Albert Harbour in 1906-07. Bernier spent another winter at nearby Arctic Bay in 1910-11, and again at Pond Inlet on his vessel the Minnie Maud in 1912-13 and the Guide two years later. But these were exploratory and trading voyages, and although Bernier carried and distributed Bibles sent by the missionaries, he made no attempts to convert the Inuit to his faith.

It remained for an Inuit man, Akumalik, to undertake that task. He had been born in Tununiq—the area around Pond Inlet—in about 1890, and eventually heard snippets of Christianity from various sources. As a curious young man, he had taken the initiative to travel to Cumberland Sound to visit the mission at Blacklead Island. By the time he did so, in the second decade of the nineteen hundreds, there were no Qallunaat missionaries remaining there; the mission had closed. But there remained a devout congregation of Inuit Christians, led by men and women who had been trained by Reverend Edmund Peck—Uqammak to the Inuit—and his followers, Julian Bilby and E. W. T. Greenshield. One of those Inuit, Peter Tulugarjuaq, baptized by Peck in 1904, was always mentioned by the missionaries as a capable and devoted convert.

We will never know exactly what Akumalik learned of Christianity while at Blacklead. But when he returned to Pond Inlet, it was with Bibles and some knowledge of their contents.

Akumalik’s wife, Arnaujaq, was the sister of Takijualuk, known to traders as Tom Kunuk. He worked for a rival of Captain Bernier, Captain Henry Toke Munn, who had a post at Button Point on Bylot Island. Munn got to know Akumalik well.

Munn thought that Akumalik was very intelligent. In the usual patronizing way in which he wrote about Indigenous people, he described him as “an excellent native,” but he thought his explanations of the Christian faith were vague and crude, only enabling his followers to tack the new beliefs onto their older ones.

Munn’s comments, though, have to be understood in the context of his own beliefs—he opposed Christianity vigorously. “I frankly prefer … the unconverted native Eskimo,” he wrote, adding, “and I think his own animistic ‘religion’ fulfils best his simple needs.” Of his associate, William Duval, who had spent half a century among the Inuit, Munn said he “considers the unconverted native to be more truthful, self-reliant, honest and kinder to his old people and children. He has found the unconverted native always more generous in sharing his food in times of hunger.”

Munn noted that those among Akumalik’s followers who were able to speak the English jargon that Inuit used to communicate with traders used the odd expression “coming up Jesusy” to describe their embracing of the new faith.

Akumalik actively proselytized in the region, and made many converts. Two of them were the father and son team of Umik and Nuqallaq. They modified what they learned to suit their own purposes, and took it to the Igloolik area, converting many Inuit there.

Akumalik travelled extensively by dog team, bringing his message to scattered hunting camps. People remember one of his eccentricities: when he wanted to pray with the people in public, he would stand facing them, then look down at the ground and move around in a circle the way a dog does when preparing to lie down.

During the winter of 1921, Tom Kunuk often asked Munn to explain the “Tree-ni-tee.” Munn was perhaps not the best choice for religious instructor, but he nonetheless made an attempt at answering Tom’s questions. That winter a young widow who had recently converted to Christianity became pregnant. She insisted that she had had nothing to do with a man since her conversion; inspired by stories of the virgin birth, she claimed that her child-to-be was a “Jesusy baby”.

What developed in northern Baffin and the Igloolik area was a crude form of Christianity, manifested, in the words of one author, in “singing hymns and reading bibles, in shaking hands and waving white flags.” It has been described as a “weird blend of Anglicanism and Inuit spirituality.”

Akumalik remained in the Pond Inlet area for the rest of his life. In 1929, white missionaries finally arrived. Coincidentally, Anglican and Catholic missionaries both arrived at the same time. The unfriendliness shown to each other by these competing men of the cloth can only have confused the Inuit even more about the message of love that the church claimed to bring.

Akumalik’s son, Joseph Idlout, was born in 1915. Although he grew up to be a powerful hunter and camp boss, Idlout decided in 1955 that he and his family should move to Resolute where paid employment was available. Akumalik disagreed, aware that alcohol abuse was rampant at the air base there, and argued with his son over this. But Idlout was determined, and left his camp with his wife and children to travel to Arctic Bay to catch the ship that would take him to Resolute. Despondent, Akumalik put a gun to his head and ended his own life that same day.

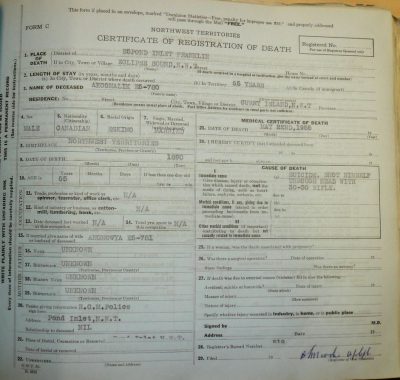

Akumalik’s death certificate, telling of his suicide on May 22, 1955. (Photo from Kenn Harper’s collection)

Taissumani is an occasional column that recalls events of historical interest. Kenn Harper is a historian and writer who lived in the Arctic for over 50 years. He is the author of “Minik: the New York Eskimo” and “Thou Shalt Do No Murder,” among other books. Feedback? Send your comments and questions to kennharper@hotmail.com.

I headed the Qikiqtqnii Truth Commission, the horrors’ we heard was horrendous.

I just learned for the first time of my great grandfathers suicide, by this article. This descendant is in awe of the privilege of the author to all this information.

There is no privilege. Just research. It was never unknown.