Inside prison, art helps Nunavut women heal

“Totally essential for the mental health of inmates”

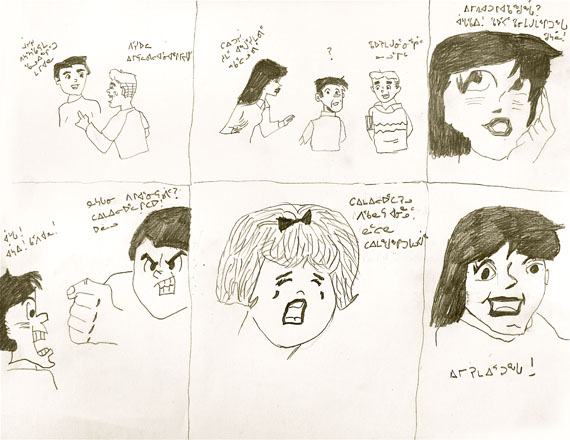

This take on the Archie comic strip tells a story about family violence. (IMAGE COURTESY OF PASCALE ARPIN)

Pascale Arpin, who runs a volunteer art program at the Nunavut women’s correctional centre. (PHOTO BY SAMANTHA DAWSON)

Most of the time, Pascale Arpin never gets to say goodbye to the women she meets at the Nunavut women’s correctional centre in Iqaluit

“I’ve never actually had a chance,” said Arpin, the creator of an art program at the jail called “Art on the Inside,” and volunteers her time teaching inmates how to draw, paint, and do sculpture.

The best day: when she brought an Arctic char to the two-hour weekly meeting, and asked everyone draw it as a still life.

“That was our male model,” Arpin said.

Though the program is on hold for the summer, it will start again in the fall.

Arpin, 24, approached NWCC with the idea and has been putting on the program since January.

Originally from Ottawa, Arpin said working with vulnerable populations she’s always been interested.

And that’s despite the high turnover of participants in her program.

The guidelines for the program are simple: respect, encouragement, and freedom of expression, meaning no censorship regarding the content of the art.

But Arpin, who moved to Iqaluit a year and a half ago to work as an educator at the Centre for Early Childhood Education, says she isn’t looking to provide the inmates with an art therapist.

She just chats with them about what they want to chat about — and they don’t talk about the offences they’re convicted of.

One of the first assignments Arpin handed them was to draw ookpiks, since she owns an extensive ookpik baby owl collection.

Arpin said she saw technique improvement in the same day, for example, a two-dimensional drawing being given shadowing and becoming three-dimensional.

Each week, the participants would show her their completed artworks.

“The guards have told me they are always really proud to show their stuff,” Arpin said, so finding money to carry on the program would be a positive thing “because when I do become too busy to do it or if I move, I want someone else to take it on.”

Even just having a supply of art materials at the facility would be good.

“I’m pretty sure I’m the first one to purchase material,” she said, of an art run she did to Ottawa.

And it’s helped. The outcome is rehabilitative, because the art addresses elements of anger management, stress release, coping, and healing.

“I think these programs are totally essential for the mental health of inmates,” Arpin said.

The art helps with self-perception and identity in a place where you are wearing the same clothes and eating the same food, Arpin said. “You get to see the person outside of the inmate.”

Olayou Jaw, a former inmate, started the program in January and participated until April. Before she was released, she made a sketch of an Archie comic book during one of Arpin’s art exercises.

One panel in her comic depicts a character who is abused by her common-law partner, who gets beat up by a brother. “That other lady, she took off,” Jaw said.

The comic represents her struggle and desire to stop drinking: “next thing I was drawing to myself, and I said I don’t want to drink anymore more because I’m sick. That was my story,” she said of the comic.

“I still got that art in my house,” said Jaw, 34. “I showed it to people around my house. They did like it, even alcoholics.”

Doing that was relaxing — “Betty and Archie and me,” Jaw said with a laugh.

“It was fun,” she said, adding that it made her feel better.

Sometimes Jaw runs into Arpin in Iqaluit, and “when I saw her, I told her I want to still work with you,” Jaw said. “I miss her too.”

(0) Comments