Taissumani, Aug. 17

A well-travelled Inuktitut Bible

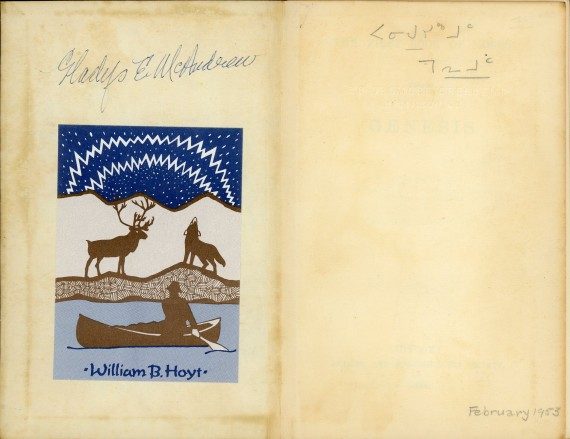

The inside front cover of a particularly cherished book in Kenn Harper’s collection—an Inuktitut Bible. (PHOTO BY KENN HARPER)

I collect Inuktitut Bibles, among other rare Inuktitut-language items. The older the better. But one of the most treasured items in my collection is not terribly old.

It is a copy of “The First Book of Moses Called Genesis,” published in London by the British and Foreign Bible Society in 1934. It is bound in black with no decoration except two gold-stamped words on the upper right cover, saying “Eskimo Genesis.”

What you know about the earlier owners of a book is called the book’s provenance. And this book has a most interesting provenance, which is very personal to me.

I first saw the book many years ago in Toronto, when the well-known Arctic collector George Luste invited me to his home to see his library. I spotted this lovely volume and knew that I had to have it.

Let me describe first what peculiarities of this particular volume interested me. Pasted on the inside front cover is a bookplate bearing the name William B. Hoyt. Above that, in pen, is the signature Gladys E. McAndrew.

On the next page, the front fly-leaf, which is otherwise blank, is an inscription in Inuktitut syllabics, and then an address in Hamilton, Ontario, which is embossed in raised uncoloured lettering and, so, is barely visible in the photograph above. At the foot of that page is the date “February 1953.” On the reverse of the end fly-leaf, at the back of the book, are three lines of syllabics, followed by a date.

Why did these details excite me?

The writing in syllabics on the front fly-leaf said, when transliterated into roman orthography, Panigusingmut Mairimut. We’ll forgive the writer his one error—the first word should have been Panigusirmut. This means To Mary Panigusiq.

Young Inuit today would probably only add the directional suffix “mut” to the last of her two names, but it was common at the time to add it to both. This name meant something to me, because Mary Panigusiq was the name, before marriage, of the woman who became Mary Cousins. And she was my mother-in-law.

The inscription had been written by someone who was giving or sending this book to Mary, and the date at the foot of the page, February 1953, told when.

Now to the three lines of syllabics on the end fly-leaf. They are written by a different hand, with only a few finals. Transliterated into roman orthography, they read as follows:

Ajuriqsuijimit

Naksiujjusiakka

Kuriapamiiluta

Translated they mean: The gift that was sent to me (carried to me) from the minister when we were living at Craig Harbour (Kuriapa). So Mary wrote this herself.

And when did this happen? The next line tells us: May 13, 1953.

Who was this mysterious minister? The use of the word “ajuriqsuiji” tells us that he was a Protestant minister, not a Catholic.

And the dates—February 1953 for the inscription by the missionary, and May 13 of the same year for Mary’s receipt of it, or at least the date that she wrote in it—tell us that the book must have been carried in a spring packet of mail by dogsled to Craig Harbour on Ellesmere Island, for the date is far too early for the arrival of a ship.

The nearest community with a mission was Pond Inlet, and it happened to be Mary’s home community. She knew the minister there, and for three years she had even attended the mission school run there by his wife. So the minister can only have been Reverend Tom Daulby.

Mary was 15 years old in 1953. She had moved with her father, Lazaroosie Kyak, an RCMP special constable, and her mother Letia, and their family, as well as her uncle Joe Panipakuttuk and his family, to Craig Harbour two years earlier to assist the white police officers who had reopened the police post there, which had already been abandoned twice.

Historically, Canadian Inuit had not lived that far north, and the places where they lived and travelled had no traditional Inuit names. So Mary’s writing in syllabics of “Kuriapa,” was simply an Inuktitut transliteration of the English name Craig Harbour. (Say it aloud—it works.)

At ship-time in 1953 Mary left Craig Harbour and moved to Hamilton, Ontario, a move arranged by her father with assistance from his trusted friend, RCMP Inspector Henry Larsen. Mary knew Larsen well, having travelled through the Northwest Passage with him in 1944, at the age of six, aboard the RCMP schooner St. Roch.

She would spend five years in Hamilton, attending school and visiting the many Inuit who were at the tuberculosis sanitorium. It was in this way that she preserved and even added to her knowledge of Inuktitut.

This takes us back to more information contained in the Inuktitut Bible. Mary lived with the family of Gladys E. McAndrew, whose name is on the inside front cover and whose address—38 Dromore Crescent, Hamilton, Ontario—is embossed on the front fly-leaf. That’s the address where Mary lived.

So how did this Bible come to be in the library of George Luste in Toronto? At this, I can only guess. Mary eventually left the McAndrew home. It is unlikely that she gave such a treasured possession to Mrs. McAndrew. Probably she lost it in the house. At some later date Mrs. McAndrew would have found it.

Eventually, I assume, she sold it to a book dealer who sold it on to William B. Hoyt, a well-known Arctic collector who lived not far away in Buffalo, New York. Hoyt died in 1992 and George Luste eventually bought his collection.

Because the book had meaning for me, I eventually convinced George to sell it to me in 2006. That Christmas I gave it to Mary as a Christmas gift. She was very ill with cancer. Tears filled her eyes as she saw her old Bible again, and read her own youthful notation in the back. Four months later, Mary passed away. Shortly before her death, she gave the Bible back to me, to remember her by. It is a cherished part of my book collection to this day.

Taissumani is an occasional column that recalls events of historical interest. Kenn Harper is a historian and writer who lived in the Arctic for over 50 years. He is the author of “Minik, the New York Eskimo” and “Thou Shalt Do No Murder,” among other books. Feedback? Send your comments and questions to kennharper@hotmail.com.

(0) Comments