Southern Inuit youth show high rates of prescription drug abuse: study

But research shows schools can offer a protective effect, researcher finds

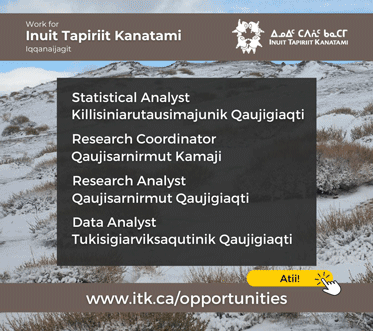

This graph from a presentation delivered earlier this year by Dr. Cheryl Currie of the University of Lethbridge shows the differing rates of prescription drug abuse among non-aboriginal youth, 12 to 17, Métis, First Nations and Inuit. (GRAPH COURTESY OF C. CURRIE)

One in five Inuit youth aged 12 to 17 living in southern Canada and who were surveyed in a study of 45,000 adolescents across Canada use prescription drugs to get high — a rate that’s three times higher than among non-aboriginal youth.

That’s among the findings of a study on the adolescent use of prescription drugs to get high in Canada and what role the school environment plays.

Detailed results of the study, by Cheryl Currie at the University of Lethbridge, will be published November 2012 in the Canadian Journal of Psychiatry.

Currie’s study looked at data from the 2008-09 Youth Smoking Survey, which asked students how often they have used the following to get high and not for medical purposes over the past year:

• sedatives or tranquilizers (such as Valium, Ativan, Xanax);

• prescription pain relievers (such as Percocet, Demerol, Oxycontin); and,

• prescription stimulants (such as Ritalin, Concerta, Adderall).

Overall, 5.9 per cent of Canadian adolescents surveyed said they had used prescription drugs to get high in the past year.

Of those, 40 per cent used drugs from several categories for that purpose.

The survey found no difference between prescription drug use among girls and boys.

But girls were more likely to use prescription pain relievers and sedatives or tranquilizers to get high, while boys were more likely to use prescription stimulants for this purpose.

But the rate of prescription drug abuse among the 381 Inuit surveyed was three times higher than for non-aboriginal youth, more than double the rate among Métis and still higher than that of First Nations youth.

No data was collected in Canada’s North or within aboriginal communities such as reserves.

But the study showed Inuit youth who live in southern Canada may be engaging in high levels of substance abuse.

Currie said her research suggests Inuit youth feel much less connected to school than other Canadian children living in these areas.

“Low school connectedness is strongly associated with increased substance use and other problem behaviours among youth internationally,” said Currie, noting that the Centres of Disease Control has published a document summarizing the strength of this evidence.

“The findings suggest that Inuit youth in particular do not feel safe at school, and that teachers are not treating them fairly, etc. Taken together, these experiences are called “school connectedness,” that is, the extent to which students believe that adults and peers in school care about their learning and well‐being, Currie said in an email.

An earlier study by Currie on prescription drug abuse in Alberta found adults, students at college or university, those who are disabled, and those with other addictive problems most likely to abuse prescription drugs.

Currie’s research on adolescents concluded that for schools to meet their needs, adolescents have to feel safe, accepted and supported by others at school, and that this experience of school connectedness may be particularly protective for aboriginal youth.

“The good news from my study is that if we can work together to ensure that Inuit youth feel safe, secure, and are treated well by teachers in southern areas of Canada, the statistical results suggest it could have a powerful effect on reducing prescription drug abuse among Inuit youth,” Currie said.

Among those who were surveyed, twice as many Inuit youth as non-aboriginal youth said “teachers don’t treat me fairly” and “I don’t feel safe at school”

More Inuit youth also said “I don’t feel part of my school” and “I don’t feel close to people at my school” than other adolescents in Canada.

A feeling of “school connectedness” was associated with an 83 per cent reduction in the likelihood of prescription drug abuse among Inuit.

So a “particularly promising protective factor” is school connectedness because children in schools that promote connectedness are more likely to engage in healthy behaviours and succeed academically, Currie says.

To better connect, schools can encourage positive classroom atmosphere, student participation in extracurricular activities and use “tolerant disciplinary policies.”

(0) Comments