Toronto’s trove of Inuit art spans centuries

Visitors “affected by the soul of it”

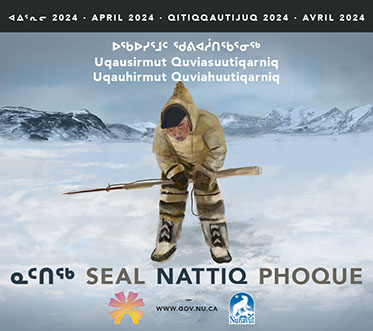

The museum’s bright, white space is meant to evoke the feeling of being on the tundra. Displayed here, the sculptures of artists Abraham POV, John Tiktak and Osuitok Ipeelee. (PHOTO BY SARAH ROGERS)

Toronto’s museum of Inuit art has operated since 2007 as the only public institution devoted to Inuit art. (PHOTO BY SARAH ROGERS)

TORONTO – Inuit and Inuit art fans may not know that one of the country’s southernmost cities holds an impressive collection of Inuit art treasures.

The three-year old Museum of Inuit art sits at Toronto’s Harbourfront Centre– and it contains one of the largest public displays of Inuit art south of the Arctic.

Jane Schmidt, the museum’s assistant curator, shows off a white and brightly lit alcove in the Queen’s Quay terminal along the harbour.

The white space, which has won a couple of design awards, is meant to evoke ice flows, snow drifts and the wind-swept tundra.

Schmidt says it helps to “set off” the art work.

It also helps visitors to the museum and adjacent gallery transition to a quiet space from the busy shopping centre outside.

In the museum are more than 300 pieces of Inuit art spanning the last 1,000 years— and most of its collection is on loan.

The older art, dating from the Thule period (1000 to 1850) is mostly unidentified work showing a traditional lifestyle.

But, as you move through the museum’s sections, the art through the 1800s changes, influenced by the Inuit trade and contact with Western civilization.

Most Torontonians — most southerners for that matter — don’t know much about Inuit art, Schmidt says.

But once they see it, she adds, they’re hooked.

“You get people who have been to the Arctic for a week and have been profoundly affected and impressed by it,” she says. “I think what the museum does it show the variety of work (from across the North.)

“Whether they’re tourists or locals, they’re affected by the soul of it.”

From time to time, the museum offers free admission on weekends, attracting hundreds of visitors.

At the beginning of the summer, the museum featured the work of Cape Dorset artist Kananginak Pootoogook. The exhibition displayed five decades of the artist’s sophisticated, larger-than-life prints.

Descriptions of each of his pieces have been translated into English and displayed by each work, offering an insight into the artist’s inspiration.

Pootoogook often depicts the caribou in his work; one print in particular shows the animal looking straight ahead with a human-like expression.

That moment Pootoogook describes as the “warm feeling you get starting from your forehead and up over your scalp.”

“(This exhibition) is a real direct example of what we’ve been able to achieve,” says David Harris, the museum’s director. “Pootoogook is one of the most compelling artists in Inuit history… and this is his first solo exhibition in a public institution.”

Harris is the force behind the creation of the MIA, the seed of which was planted in the few years he went to work in Cape Dorset.

Straight out of university, Harris applied to teach with the Baffin divisional board of education, arriving in Cape Dorset in 1996.

“I knew about Inuit art from visiting the Art Gallery of Ontario as a youth, but I certainly didn’t have the sense of the depth of art being produced in Cape Dorset,” he says. “I remember being so impressed, in awe, really.”

Two years later, he returned to Toronto with a young family and found few teaching jobs awaiting him.

But something from his experience in Cape Dorset stuck.

Harris read an opinion piece in Inuit Art Quarterly one day, written by a former co-op manager there that said it “would be a shame that Inuit art would have to be re-discovered.”

Soon afterwards, Harris opened the Harris gallery on Toronto’s waterfront.

Ideally, he says, the gallery would grow to become a public institution and in 2007, the Harris gallery became the Museum of Inuit art.

“I realized that Inuit art hasn’t been at the forefront of exhibitions,” Harris says. “I get the impression that, on all levels, Inuit artists are moving outward. We can be a catalyst for that.”

But as far as education goes, what can a museum thousands of kilometres away from the artists themselves have to offer?

The museum’s head curator, Ingo Hessel, keeps the institution relevant through direct contact with Inuit artists, Harris says.

More than two decades ago, Hessel began a relationship with the North, working in the Inuit art section of the federal department of Indian and Northern Affairs.

Hessel still visits Inuit artists, co-operatives, wholesalers, museums, galleries and researchers across the Arctic.

“I don’t pretend to speak for Inuit artists but I try to make a conscious effort to convey…them to a southern audience,” Hessel said. “We have to attune ourselves to what they’re telling us.”

The Museum of Inuit Art is located at 207 Queen’s Quay West in Toronto. The MIA is open daily from 10 a.m. — 6 p.m. and adult admission is $6.

(0) Comments