Researchers surprised to see Rankin Inlet lakes releasing fewer carbon emissions

Climate change is causing many lakes to release more CO2, but “these lakes in Rankin Inlet have gone in the opposite direction”

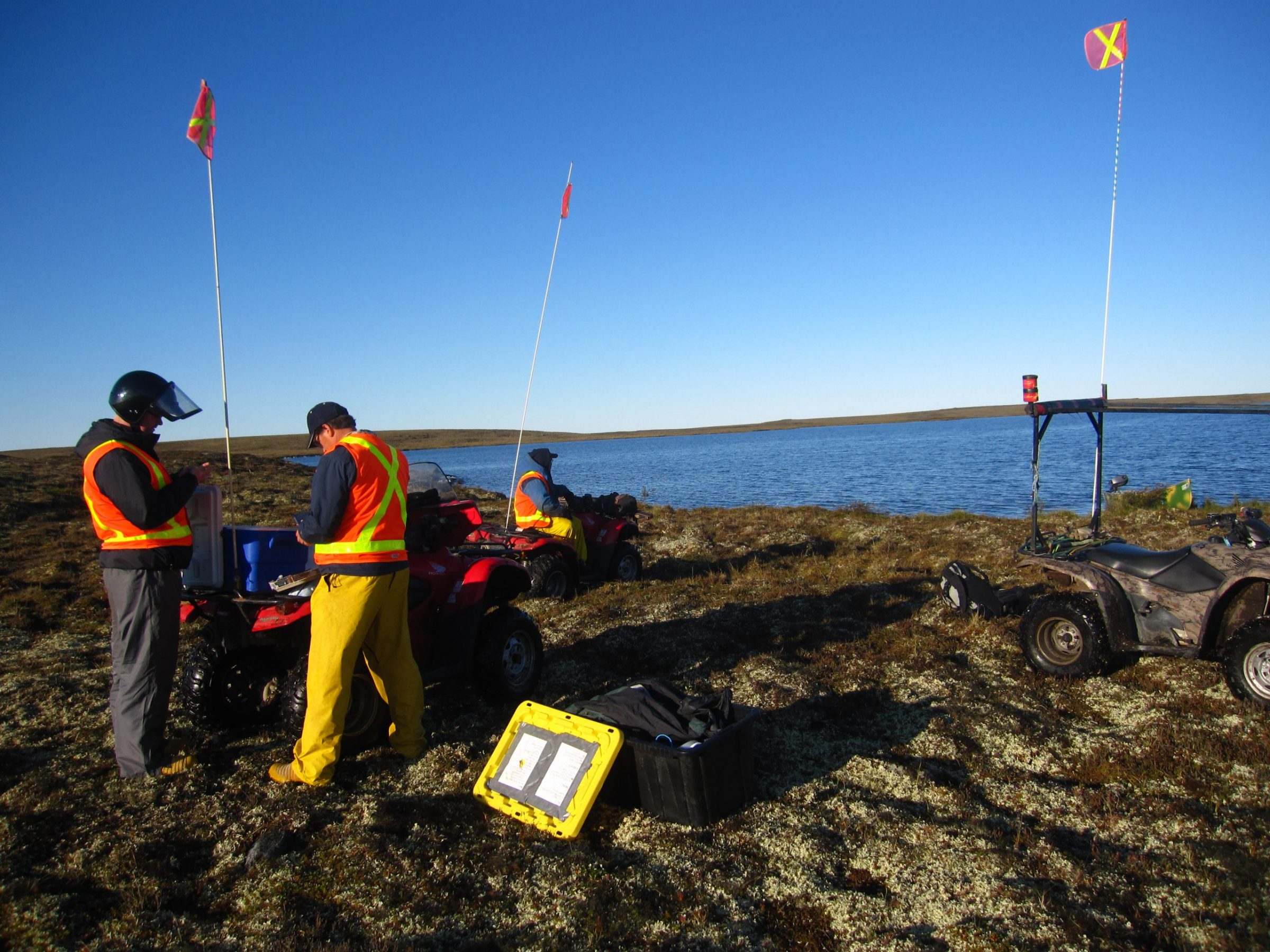

Three researchers from the University of Guelph tested levels of CO2, a gas that causes global warming, in lakes near Rankin Inlet over four years and compared it to data collected since the 1990s. They found the lakes are releasing less carbon dioxide than nearly three decades ago. (Photo by Soren Brothers)

Researchers with the University of Guelph were puzzled by how lakes near Rankin Inlet have been releasing less carbon dioxide into the environment as the climate warms, rather than more, as expected. So they decided to take a closer look.

Their findings, recently published in the journal Global Biogeochemical Cycles, confirm that CO2, a greenhouse gas that causes global warming, isn’t being released from the lakes as much as it was nearly three decades ago.

The team of three’s unexpected findings are a piece in the puzzle of understanding global warming and what’s to come, according to lead author Soren Brothers.

The study is based on 23 years of data on lakes in the Meliadine Lake Peninsula, about 15 kilometres from Rankin Inlet.

“You don’t see that kind of long-form data very often,” said Brothers, who was helping with research for Agnico Eagle Mines Ltd. as a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Guelph when numbers from the 1990s caught his eye.

Typically, lakes release more CO2 as the weather gets hotter, but Brothers found that, on average, the 19 lakes studied are emitting less, and most contain the same amount of the gas as their environment.

“That’s what we were surprised to see … these lakes in Rankin Inlet have gone in the opposite direction,” he said.

The researchers have several guesses for why the lakes are releasing less carbon dioxide.

One is that, as these lakes see longer periods without ice on their surfaces, the growing seasons for underwater plants have lengthened, and these plants are able to store more carbon, said Brothers.

Another explanation has to do with Nunavut’s rocky landscape and thin soil.

In other northern areas like Alaska, plant material in permafrost accumulated over centuries thaws and enters lakes, where it’s converted to carbon dioxide and methane.

This may not be happening nearly as much in Nunavut, where permafrost doesn’t store as much organic carbon, meaning local lakes aren’t being supplied with extra food.

Early data on the lakes from 1994 to 2009 came from a report for a proposed gold mine in the area, which the researchers got from the Government of Nunavut, and the data from 2009 to 2015 came from Agnico Eagle.

The researchers took their own samples from the lakes in the summers between 2014 and 2017.

Brothers said for now, it is difficult to predict whether the lakes will start releasing more carbon in the future.

The North is important in climate change research because the Arctic has been warming faster than the rest of the world for decades and lots of carbon is stored in permafrost, the study states.

Brothers said he would like to do another research project that could help northerners plan for the local impacts of climate change.

(0) Comments